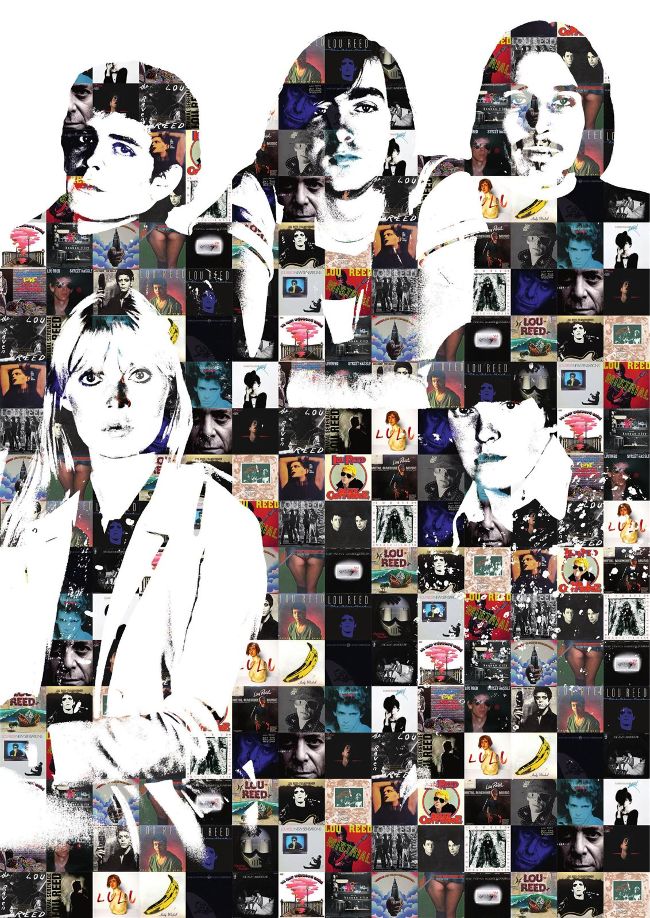

BETWEEN THE GUTTER AND THE STARS

A 20-PAGE CELEBRATION

THE 50 GREATEST LOU REED AND THE VELVET UNDERGROUND SONGS

IT WAS A DIRTY JOB, BUT SOMEONE HAD TO do it. Possibly he had no choice.

Lewis Allan Reed’s contributions to rock’n’roll were unique and compelling, but it also seemed that he was compelled. The steady gaze he trained on the sides of life others found uncomfortable – drugs, sex, violence, poverty, human folly and desperation – seemed at times his real addiction, although there were others.

Born in Brooklyn in 1942 but raised in exile in suburban Freeport, Long Island, he was electrified first by doo wop and R&B, then by ECT as his parents sought a cure for what were considered aberrant behaviours. Later, his fluid sexuality, narcotic experiments, brooding defiance and zeal for fearless literature were embodied in The Velvet Underground, whose four Lou-fronted studio albums invented the idea of a pop music that opposed the mainstream. With avant-garde input from violist John Cale, Bo Diddley propulsion from drummer Moe Tucker and the versatile support of guitarist Sterling Morrison, plus contributions by German singer Nico and, later, Doug and Billy Yule, the VU were capable of unprecedented sonic assault, ballads of trembling longing, and joyous paeans to the force they channelled: rock’n’roll.

Lack of success in their time drove Reed to leave the VU, but his solo career rarely pandered.

Transformer, the exquisite 1972 album he made with David Bowie, was the hit he often disavowed.

Rather, he would follow his passions – for feedback, for Edgar Allan Poe, for Tai Chi – whether or not fans went with him. Often he seemed to prefer a lonelier path; other times – as when honouring friends and mentors Andy Warhol and Doc Pomus on Songs For Drella and Magic And Loss – asofter,

humbler Reed would allow himself to be seen. Ultimately, he resisted explanation or typecasting of any sort.

Ten years since he passed from liver disease aged 71, his implacable spirit lives in the 50 songs that follow…

Illustration by Clayton Hickman, Sarah Hampson and Mark Wagstaff/Alamy

50 THE VIEW

(from Lulu, 2011)

Metallica’s almighty noise carries Lou’s immortal commands.

“It was so impulsive,” Lars Ulrich said of the 10 days his Metallica and Reed wailed and walloped in northern California, “it’ll take me years to access what happened.” And so it’s gone for many with Lulu, the combo’s wrongly dismissed transformation of a 19th century drama about a licentious, murderous maven into poetic metallurgy. The View is their masterful power play, its threeguitar roar the forged shield upon which Reed inscribes his demands –sex and submission, omnipotence and awe.

GHC

49 EDGAR ALLAN POE

(from The Raven, 2003)

A descent into the maelstrom.

Reed’s idea to re-imagine Poe’s life and work in an experimental double-LP of songs and poems stemmed from a 2000 theatre production. With commendable perversity, the piece’s signature rocker, Edgar Allan Poe – horn-driven, raunchy and joyously cornball as it describes a litany of “carnage”, “decapitations”, “poisonings” – bears little relation to the spectral flow and angry metal elsewhere on the record. That Poe holds a mirror to Reed’s own interior, a similarly lively cesspit of trickery, vengefulness, fantasy and noir, suddenly seems obvious. “Not exactly the boy next door!” he trills on the chorus. Quite.

PG

48 LEGENDARY HEARTS

(from Legendary Hearts, 1983)

Troubled times, troubled song, untroubled melody.

Studio squabbling with soon-to-depart guitarist Robert Quine ensured that recording Legendary Hearts was an unhappy experience, but Quine’s insistence that Reed’s production almost erased his work didn’t always ring true, especially on the beautifully layered title track, where his and Reed’s guitars quietly duel. In contrast to the self-lacerating lyric (“I’m good for just a kiss, not legendary love”), the gorgeously lolloping melody was so catchy that perhaps for the only time in his career Reed clapped along with himself in the budget-conscious video.

JA

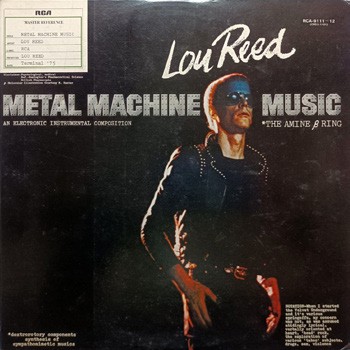

47 METAL MACHINE MUSIC, A-1 – A-4

Getty

(from Metal Machine Music, 1975)

Meticulous noise, far from chaos.

Metal Machine Music is the critical and commercial failure whose locked grooves and unrelenting influence on a halfcentury of seekers mean its sculptural screech has never actually stopped. Recorded nocturnally and alone with minimal gear, Metal finds unending beauty within New York’s endless industrial din, feedback sheets and squelching circuits creating harmonies that feel like phantoms, until they refuse to fade. Reed obviously didn’t invent harsh noise or atonal excess; within the context of rock’n’roll, however, he rightly argued it could be enough.

GHC

45 THE OSTRICH

(The Primitives single, 1964)

46 RIPTIDERIPTIDE

(from Set The Twilight Reeling, 1996)

Guitars, guitars and then some more guitars.

By the time of the dense, sprawling Set The Twilight Reeling, Reed was into texture as much as song and nowhere more so than on the album’s lengthy but exhilarating centrepiece, the very essence of his mid-’90s work. The lyric namechecks Van Gogh, but Reed paints a picture of a world out of control. More crucial are the wholly in-control guitars, where Reed cranks out a giant riff over which he deploys Glenn Branca/ Sonic Youth-style layering. Heroic.

JA

45 THE OSTRICH

(The Primitives single, 1964)

“Everybody get down on your face, man.”

As staff writer at Pickwick

Music, Reed was required to milk pop trends. Dance songs – Twist, Madison, Hully Gully – were all the rage. Most, however, weren’t introduced via such a malevolent racket as The

Primitives’ lone, ultra-rare 45. After an ersatz live intro, a Then He Kissed Me riff is laid over a stomping beat. Lou barks surreal instructions while his comrades squeal the title by way of a chorus. As deliciously crude as Louie Louie, it’s a wonder it never caught on.

JI

44 LEAVE ME ALONE

(from Live: Take No Prisoners, 1978)

A hell of an end to a hell of a show.

Reed’s Street Hassle songs, already a challenge to delicate sensibilities, are in their element on this live album to end them all. If I Wanna Be Black is the ballsiest move (what with the liberal n-wording), Leave Me Alone is the performance that turns studio lead into spontaneously unhinged scuzz-rock gold. It’s not just faster, nastier, fuzzier, and borderline unintelligible. It’s the closest Reed ever came to reanimating the sheer, libertarian chaos of White Light/White Heat-era Velvet Underground.

DE

43 LIKE A POSSUM

(from Ecstasy, 2000)

Suite for feedback and angry man.

The cover of Ecstasy appears to show Reed in the throes of orgasm – which, if nothing else, gave sceptics the opportunity to draw crude masturbatory parallels with the album’s contents.

Chief target was Like A Possum, an 18-minute squalor-fest rich with crack, butt, used condoms and “roller-bladers giving head”. Yet the gutter provocations and bludgeoning grind gradually take on a purgative, then meditative, quality – the noise-rock equivalent of a gong bath, from which you might just emerge, as Reed threatens, “Calm as an angel”.

JM

42 LAST GREAT AMERICAN WHALE

(from New York, 1989)

A Moby Dick for the Reagan era.

After a quarter-century of charting every human degradation, here was a song to silence those who believed Lou Reed amoral. To a measured strum, the singer introduces our half-mile-long cetacean metaphor, then tells how the beast causes a tidal wave, killing all nearby but a Native American chief incarcerated for shooting a mayor’s racist son (hurrah!), only then to be harpooned by an NRA “yokel” (boo!). Reed’s ensuing summation of America’s mistreatment of its natural wonders and indigenous tribes is swingeing.

AP

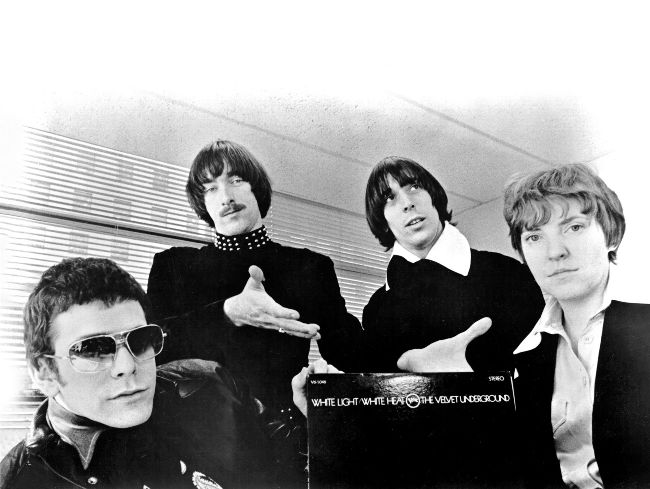

JIM WIRTH UNDERGOES THE VU’S CRO-MAGNON INITIATION RITE

Black mirror: The Velvet Underground look on the bright side (from left) Lou Reed, Sterling Morrison, John Cale, Moe Tucker, 1968.

41 SISTER RAY

(from White Light/White Heat, 1968)

Having grumbled about excessive volume throughout the recording of White Light/White

Heat, engineer Gary Kellgren’s patience snapped as The Velvet Underground prepared to make up for a shortage of material by laying down an open-ended jam with no bass underpinning. “I don’t have to listen to this,” he told Lou Reed as he reached for the tape machine. “I’ll put it in ‘record’, and then I’m leaving. When you’re done, come get me.” Thus, Kellgren opted out of 17 of the most extreme minutes of The Velvet Underground’s recording career. As Reed Dylanises about struggling to find a vein to inject into (“I’m searching for my mainline/I said I couldn’t hit it sideways”), the band turns all of the dials into the red.

Conceived by Reed on the way home from a disappointing show in Connecticut, his Alphabet City take on Hieronymus Bosch hinges around a transvestite smack dealer (named in honour of sexually ambiguous Kinks frontman Ray Davies) and a bloody murder that everyone is too strung out to notice. As he explained: “The situation is a bunch of drag queens taking some sailors home with them, shooting up on smack and having this orgy when the police appear.”