HOW TO BUY

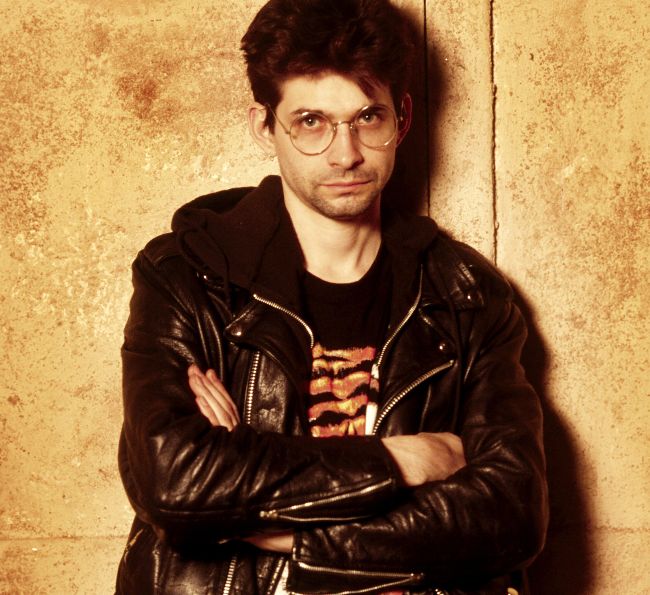

Steve Albini

Big Black to Shellac, the Chicagoan iconoclast’s own recordings.

By Andrew Male.

The Proprietor:

Steve Albini, brilliant yet unknowable.

“WE KNEW Big Black were going to be making ugly, obscene music,” Steve Albini told Toronto filmmaker Daniel Sarkissian in 2020, “noisy music [with] limited appeal… There was no point in entertaining notions of popularity.” Initially conceived as a one-man project in 1981 in Chicago, Illinois, where Steve Albini was a journalism student at Northwestern University, Big Black began as an exercise in dissident misanthropy, inspired by the aggressive electronic minimalism of Tuxedomoon and Cabaret Voltaire; out-of-phase cheesewire guitars and militaristic machine rhythms allied to Albini’s in-character lyrics, nightmare reportage from the dark heart of a corrupted America.

However, as Albini himself insists, the ‘group’ didn’t truly exist until he was joined by guitarist Santiago Durango of Chicago punk band Naked Raygun, and later, bassist Dave Riley.

The Big Black sound developed around the high, chiming train-yard wail of Durango’s Telecaster guitar – played through a distortion pedal and a Fender Twin amp – the relentless attack of the Roland TR-606 drum machine and Riley’s bass sound, marinaded in the cosmic slop inf luences of Funkadelic. Albini heightened the high-tensile sound by issuing twin-headed thin-copper guitar picks that hit the strings twice for “a sharp, zinging attack”.

“There was no point in entertaining notions of popularity.”

When Big Black folded in 1987, they had become popular, the aggressive sound, misanthropic lyrics and coiled, skinny violence of their live performances attracting what Albini called “people [who saw] your music as an expression of their ugliness and hatred.”

Rather than mitigate that response, Albini doubled down.

His next group, formed with Scratch Acid rhythm section David Sims and Rey Washam, were named Rapeman, after a Japanese superhero manga comic.