PUTTING YOUR FAMILY HISTORY INTO CONTEXT

No family lives in a bubble! Our lives are shaped, and even completely changed, by context – what goes on around us. Here professional researcher Kim Cook shows you how to gain a much richer feeling for your ancestors’ lives by exploring the five key research elements you really need to know about…

DISCOVER YOUR ANCESTORS’ WORLDS

5 KEY RESEARCH APPROACHES TO ENRICH YOUR GENEALOGY

First let’s think about what context is in terms of ‘family history’. Context starts with family, spreading out to the local, the regional, national and international, impacting in varying degrees on family life. To understand the events that shaped the lives of our ancestral families, we need to consider these five elements of context.

1. Family

Documents give us the facts of our ancestors’ lives, but it’s not necessarily obvious why their lives shaped up as they did. For that, we need to dig deeper, studying and interpreting documents from wider sources alongside each other.

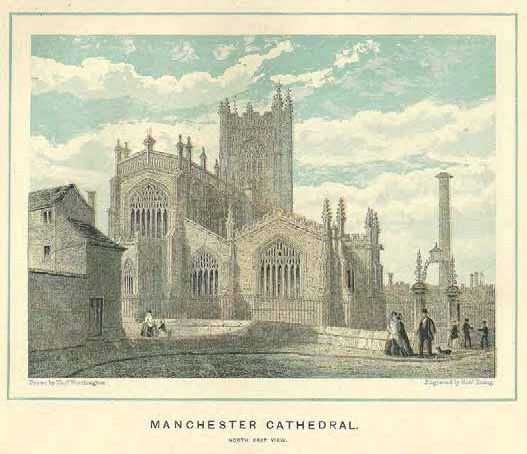

Manchester Cathedral was one of many churches popular with couples who wished to avoid opposition to their marriage

What can parish registers reveal?

Parish registers from 1538 until the 20th century give us essential information, but studying them the old-fashioned way, page by page, can give even more insight.

Reading all baptisms for the relevant period may reveal children born outside wedlock or from a previous marriage, those who died young, without featuring in a census, or children who lived with other family members, changing the family dynamic.

With no relationships shown in the 1841 Census, some children in a family may be step-children, nieces, nephews, or grandchildren.

Examining all marriage entries may reveal family members witnessing other marriages. Were these other couples extended family, friends, or colleagues? If the same witness name crops up repeatedly, was he a parish clerk or churchwarden?

When an expected family marriage isn’t found, a search of banns should indicate the parish where it took place. Where there are no banns for a missing marriage, this suggests opposition, impediment, or bigamy. A couple facing family opposition would pay for a month’s lodgings in a distant parish and have banns called there. Once banns had been called three times, the couple could marry there. City churches, including St Martin in the Fields, London, and Manchester Cathedral, were noted for such marriages.

Hints of legal issues

Legal impediments were a tougher hurdle, particularly when there was a prohibited blood or marital relationship (as listed in the prayer book, Table of Kindred and Affinity), between bride and groom. Where a widow or widower wished to marry the sibling of the deceased spouse (forbidden affinity), the couple, and often close family, had no option but to move far away, permanently, where the previous marriage was unknown.

Escaping a bad marriage was legally impossible for most people until 1857, and even then it was expensive and difficult. The only way was for one of them to move away, and become known as single or widowed. If another love bloomed, any marriage was legally bigamous, although bigamy was rarely uncovered.

If one branch of the family suddenly moved far away, with no obvious occupational reason, investigate marriages in the new district to see whether there was a legal impediment because of affinity, or a pre-existing marriage.

Finding family disasters

Illness, incapacity and death were major family disasters. Physical or mental incapacity should have been recorded on census returns from 1851. This often didn’t happen with youngsters, but later returns may show an incapacity as being ‘from birth’. When a worker living in a tied home died, eviction was highly likely. The grief of bereavement, accompanied by swift and often callous removal from home, was horrendous. Sometimes the widow and children returned to the parental home, or that of a sibling, but could end up in an institution.

Investigating epidemics

General Register Office (GRO) death certificates state whether death was natural, accidental, or violent, and whether a post-mortem or inquest occurred. Comparison with other certificates may indicate whether an illness was long-term, familial, or part of an epidemic. Where there’s no death certificate, study all burial entries over adjacent years. Even when individual burial records say little, analysing entries over some years will provide annual and average death rates according to age and season, revealing any spikes in death rates for year, season, or age. Increased winter mortality was common in extremely severe weather, while a spike of spring deaths suggests a poor harvest the previous year, leaving insufficient food stores. An increase in summer deaths, or a cluster of deaths in one neighbourhood, both suggest infection, possibly dysentery, cholera, smallpox, or typhus.