AFTER THE STORM

Sierra Leone’s present beauty and past pain are intimately bound. A journey from the West African country’s jungles to its jade-green shores reveals a nation with its eyes fixed on the road ahead

WORDS: SAM KEMP

Palms sway above Bureh Beach;

PHOTOGRAPHS: AISHA NAZAR

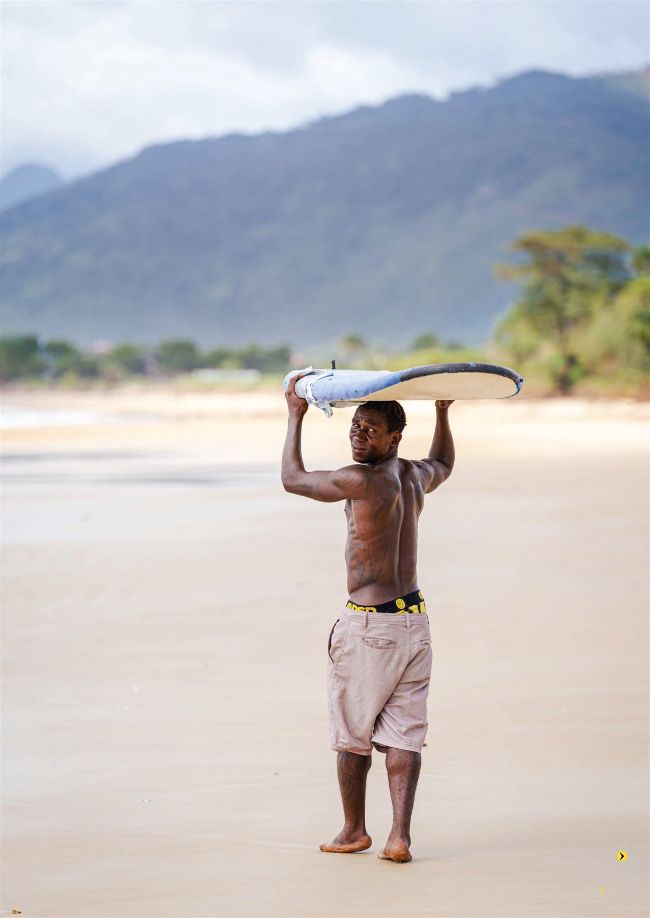

John Small, one of the founding members of Bureh Beach Surf Club

WE MAKE THE CROS SING UNDER THE COVER OF DARKNESS, THE CRESCENT PROW OF OUR DUGOUT CANOE CUT TING A FURROW THROUGH THE INK OF THE MOA RIVER.

The storm is clearing now, though the occasional bolt of lightning illuminates our passage. As my eyes slowly adapt, the world around me reveals itself in flickers and bursts: slender palms bent in prayer over the silent water; the villager to my left clutching a brace of pucker-mouthed catfish; fireflies darting like embers through the gloom.

We’re bound for Tiwai, a remote river island of 4sq miles situated in one of the last portions of ancient rainforest in West Africa. We set off from Freetown that morning, leaving the capital’s blue-green shores to follow increasingly non-existent roads east into Sierra Leone’s Southern Province. It hasn’t been an easy journey to this point, but with the first stars glimmering on the water’s surface, and the distant howls of primates all around, I feel sure I’d travel to the moon if it sounded even half as beautiful as nighttime on the Moa.

It’s a reminder that some of the most euphoric moments Sierra Leone has to offer can’t truly be appreciated without first enduring a bit of discomfort —hardly surprising given this is a nation where prehistoric forests, former slaving stations, abolitionist utopias and world-class surf all coexist within an area that’s around three times smaller than the UK.

The plan is this: after searching for Tiwai’s 11 primate species, my guide Peter Momoh Bassie and I will cross back over the river to Kambama village and return to Freetown. Occupying the seaward nib of a forested peninsula, the port city will serve as our base as we explore the islands of the Sierra Leone River and the coastal communities of the wider Western Area, visiting people and landscapes whose stories remain largely unknown to outsiders.

“I think it’s just us,” says Peter when we reach our camp: a circle of netted huts set around a jungle clearing, each furnished with several frisbee-sized spiders. This is accommodation for wildlife-lovers who regard the term ‘luxury safari’ as an oxymoron. There’ll be no sunset gin and tonics tonight. In fact, there may not even be any dinner, the freshly caught fish I had my eye on during our crossing currently bound for the wildlife research station downriver. Peter, furrowed brow framed by a military-grade crop, has gone in search of food, leaving me to quell my hunger with one of the sweet-scented oranges we were smart enough to buy from one of Freetown’s wandering street hawkers.