LOVE & VIOLINS

Instrumental rock that touches the heavens and plumbs the abyss - such is the métier of the DIRTY THREE. Four decades on their unique path, juggling side-hustles with Nick Cave, Cat Power and more, the Aussie trio reconvene to pursue "the foreign and terrifying and unknown" with Coltrane and Stravinsky in their sights. "Admittedly, that's putting a big bar up," they grant VICTORIA SEGAL.

Into the light: the Dirty Three (from left) Jim White, Warren Ellis and Mick Turner whip up a storm on-stage, Fowler’s Live, Adelaide, 2010.

Ben Searcy

"THIS IS THE DAY IT ALL STOPS.” IT’S A line that Warren Ellis often hears running through his head “like a mantra”, but in an American hotel room 25 years ago, those words were ringing in his brain at alarming volume. Dirty Three, the instrumental trio the violinist formed with drummer Jim White and guitarist Mick Turner in Melbourne at the start of 1992, were on a short US tour.

“The shows were the first time I tried to get back on the stage after cleaning up,” Ellis explains, “and the thought of being on-stage was so terrifying because I’d never been there not in some kind of altered state. I thought, OK, Warren. Listen to your body. Listen to what you need to do to get through this. And I instinctively just fell to my knees and started praying.”

From his home in Paris, Ellis outlines his other pre-show superstitions: wearing certain rings, particular jewellery, the correct colour of sock. “If an instrument breaks,” he says, “it feels catastrophic.” Yet it is this ritual – “getting down on my hands and knees, connecting with the stage, praying” – that has become his touchstone. “The moment I step into the light, hopefully a shift will take place and I’m no longer the person that I was before I walked on. And if I am,” he laughs, “I’m in trouble.”

The act of transformation is right at the core of Dirty Three’s remarkable mission. The omens were there from the start: as Ellis revealed in his visionary 2021 memoir, Nina Simone’s Gum, he found his first musical instrument, an accordion, in a rubbish dump. The trio’s first self-titled album was a rehearsal, recorded in Turner’s bedroom (known to posterity as Scuzz Studio). “Everything got born out of playing live,” says Turner, an approach that gives their records an alchemical charge.

Digging the dirt: Ellis, Turner and White, New York, 1996;

Photograph: BEN SEARCY

Dirty Three (from left) Ellis, White and Turner take a ride, 2005;

Ellis orders another bottle in the late ’90s;

The Three bring the noise at the Forum, Melbourne – “like looking at the ocean”;

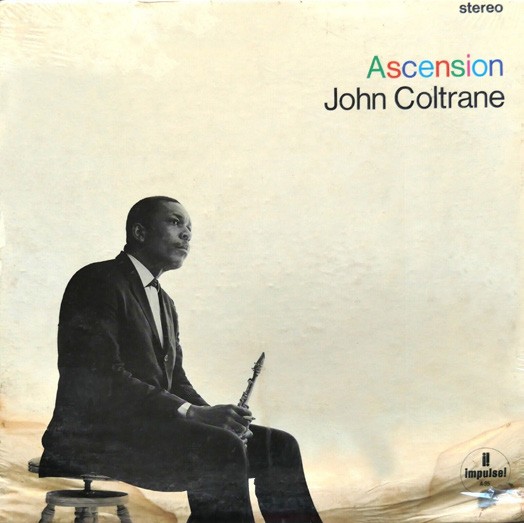

Touchstone LP Ascension;

new album Love Changes Everything;

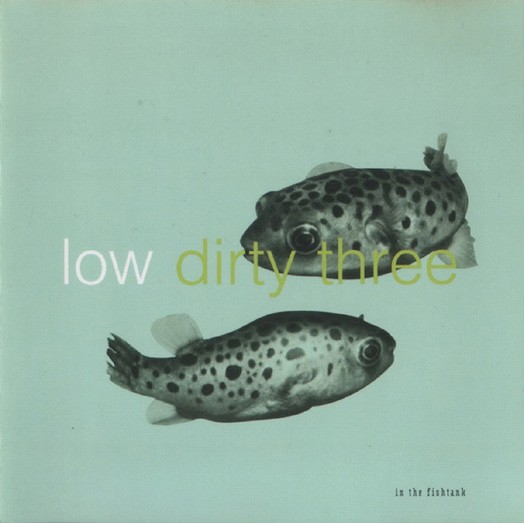

2001 Low/Dirty Three collab EP In The Fishtank.

Bob Berg/Getty Images, Jim Newberry, Dirty Three_LiveViolin, Roger Viollet via Getty Images/Roger Viollet via Getty Images

They might have emerged from the dank aftermath of Melbourne’s post-punk scene, but their wordless music blasted wonder and awe, an old-school Romanticism committed – even then – to pushing the sky away.

Bill Callahan, who has been bringing White on board to drum with him since Smog’s 2003 album Supper, witnessed Dirty Three’s first American show in 1995. “There was a big buzz about them on the streets,” he recalls, but that was nothing compared with the noise inside San Francisco’s Great American Music Hall. “I felt like I was looking at and listening to the ocean,” Callahan says. “Or a film of the ocean. Or I was a dolphin in that ocean.”