MY WAY OR THE HIGHWAY

As 2024’s Archives III box underlined, NEIL YOUNG’s late ’70s were as fertile as they were confounding. Entering his thirties in romantic and career turnaround, he hit a streak, from Zuma to Live Rust , as brilliant and unpredictable as any before or since. Along the way there’d be The Last Waltz, Like A Hurricane and “Eat a peach”. “It wasn’t about Neil trying to remain relevant,” discovers GRAYSON HAVER CURRIN. “It was him trying to keep moving as fast as possible.”

Portrait by HENRY DILTZ.

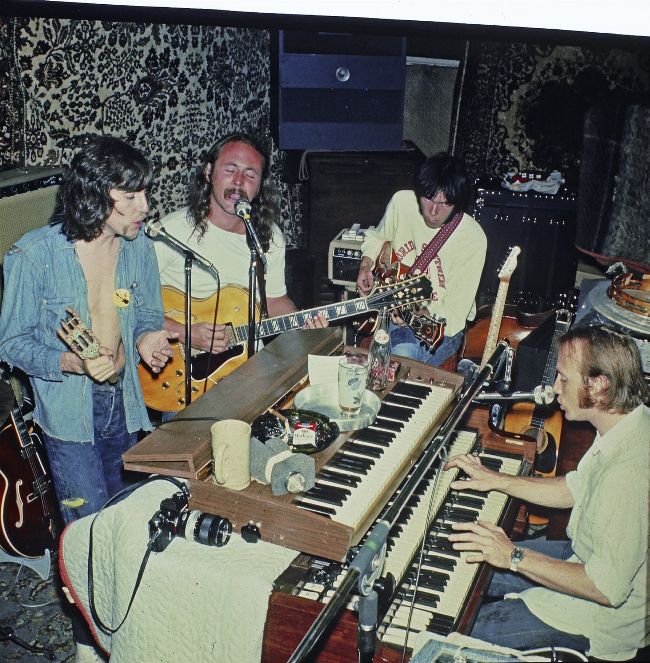

Rise and shine: Neil Young enjoys breakfast, Malibu, June 17, 1975.

Henry Diltz

IN NOVEMBER 1976, JUST BEFORE the year slumped into the Christmas holiday season, Warner Bros honchos came to visit Neil Young.

He had become the label’s most coveted rock star, not only able to dispatch albums to the top of the charts but also make critics swoon, an intersection of prestige and profitability to which few of his peers could aspire. And he was famously mercurial or, perhaps, intractable. Earlier that year, he’d bailed on a tour with Stephen Stills with one of the ’70s’ most notorious kiss-offs: “Dear Stephen, funny how some things that start spontaneously end that way. Eat a peach, Neil.”

And, suddenly, Warner Bros’s capricious star had a new vision: Decade – the three-LP compilation he’d spent more than a year building and annotating and of which a few hundred thousand copies had been pressed, due in stores in days – would have to wait.

“What if I just save Decade for a year,” mused Young, maybe a day after turning 31, to Cameron Crowe, on the road with Young and Crazy Horse for Rolling Stone. “It’s not time to look back yet.”

Instead, he wanted to release an entirely new album, American Stars ’N Bars, a primordial country-rock composite that, true to its name, suggested a wild night in some swampy dive. It could also be a vehicle for Like A Hurricane, a caterwauling theme of desperate desire Young had cut a year earlier with the re-formed Crazy Horse. “It should have its own album to be on,” Young’s fearless producer, David Briggs, recalled of the track in 1977, “instead of being released with 32 other songs.”

So far gone: CSNY, 1974 (from left) Graham Nash, David Crosby, Neil Young, Stephen Stills;

“Listening back to [CSNY at] Wembley, it is obvious that we were either too high or just no good. I am saying too high.”

NEIL YOUNG

Bob Dylan (centre) and Rick Danko (left) join Tim Drummond (second right) and Young (far right) at the SNACK Sunday Benefit, Kezar Stadium, San Francisco, March 23, 1975;

Carrie Snodgress in Diary Of A Mad Housewife;

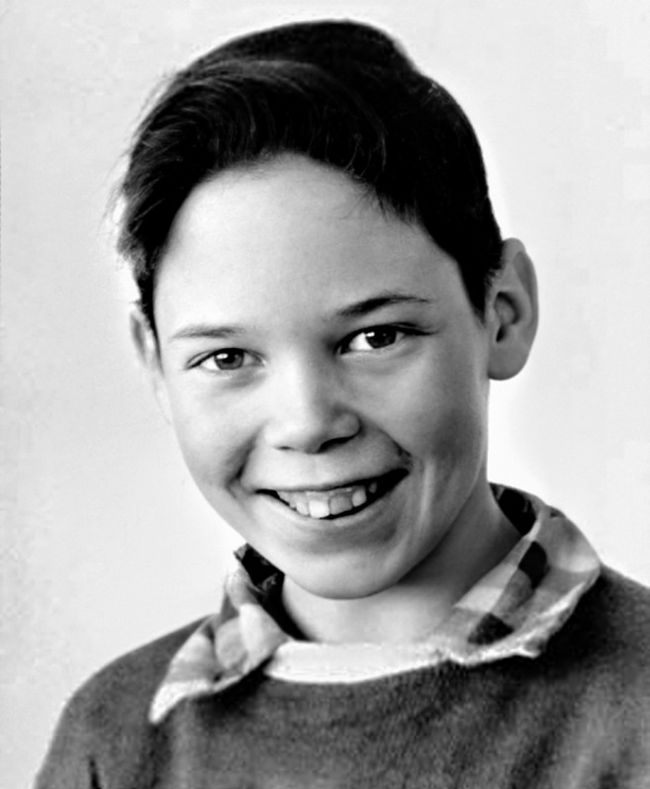

(bottom) young Neil, 1956.

RB/Redferns/Getty, Larry Hulst/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images, Cinematic/Alamy Stock Photo, Henry Diltz

Young used the bulky satellite phone on his beloved tour bus, Pocahontas, to call manager Elliot Roberts, the dogged enforcer of all Young’s realisations. Roberts called Warners; two days later, label top brass Mo Ostin and Ed Rosenblatt were on Pocahontas hearing Young’s new plan. In May 1977, American Stars ’N Bars was out; Decade finally followed that fall, almost a year behind schedule. As Briggs always told Young: “Be great or be gone.”

“Decade was the perfect example of ‘I can’t get caught here. That’s really looking back. That’s three records of looking back,’” Crowe tells MOJO nearly half a century later. Young had already compiled several of his hits for 1972’s Journey Through The Past, then been drawn into 1974’s So Far, a blockbuster pre-tour totem from Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young.

“He’s a single guy, untethered by any domesticity. And he’s a guy who had bad health, as a kid and even into Harvest,” Crowe adds. “He seemed haunted within restlessness, but that all fed this forward motion, of not wanting to get caught.”

These were the terms of what stand as the most productive and unpredictable half-decade of Young’s career, rivalled only by the preceding five years. Just consider what he did between gathering Crazy Horse’s second iteration to record Zuma in the summer of 1975 and the release of Rust Never Sleeps and Live Rust four years later, tandem capstones for a tour that suggested new possibilities for massive rock shows.

He issued his leanest and perhaps catchiest rock record ever, Zuma, and one of his most affable and accessible country records, Comes A Time. He found himself somewhere in the middle on American Stars ’N Bars, then helped invent the box set on Decade. He started a family in earnest, started a film that would challenge most every preconception of him, and started admitting that his generation of rock stars could not be gatekeepers forever. And he made at least one classic he kept to himself, the full-moon fever dream, Hitchhiker.

Young has been excavating this especially fertile span for years, with the release of Hitchhiker, the live opus Songs For Judy, and the second volume of his gargantuan Archives project. Stretching from 1976 to 1987, Archives Vol. III – ecstatically reviewed in MOJO 371 and this month confirmed among our Reissues of 2024 – makes his pace and power in the late ’70s astonishingly clear.

“I’m not an artist who could remake Harvest or After The Gold Rush,” he told a gaggle of foreign journalists a few months before that late-night call from Pocahontas. “After Harvest, I was tired of being myself, always remaking the songs on-stage… and becoming a kind of John Denver. I couldn’t stay in this state, so I wanted to destroy this idea that I had of myself.”

THE

FIRST HALF OF THE ’70S OFFERED

a string of peerless Young classics, with five albums as rich and polarised as any other sequence in rock history.

The cinematic pleas of After The Gold Rush gave Henry Diltz way to the love and faint distrust of Harvest’s folk rock and the brittle live document, Time Fades Away. The narcotised antipathy of On The Beach – an unrehearsed lecture on faithfulness, folly, and celebrity – followed. A caustic eulogy for innocence, Tonight’s The Night immortalised two of his fallen confrères – Danny Whitten, Crazy Horse’s guitarist, and Bruce Berry, a trusted roadie. The wages of success were mixed; his songs chronicled the windfalls and losses.

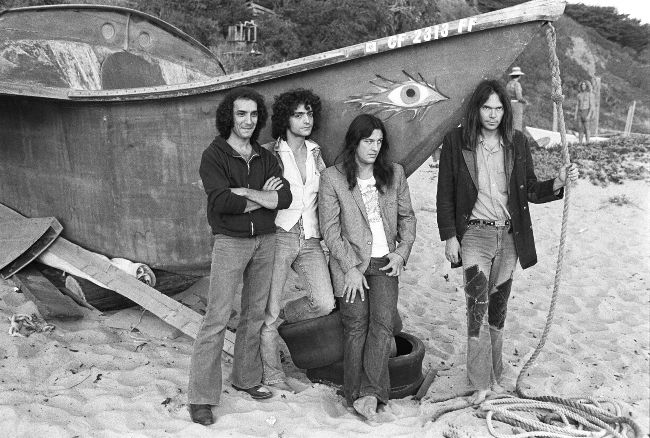

On the beach: Neil Young and Crazy Horse, Northern Malibu, November 17, 1975 (from left) Ralph Molina, Billy Talbot, Frank ‘Poncho’ Sampedro, Young.