THE MOJO INTERVIEW

With his cape and on-stage curry, he defined prog rock excess. Breakdowns, penury and near-death were the prices paid, but somehow the baroque synth lines and droll quips kept flowing… and still do. “I’m my own worst enemy,” laughs Rick Wakeman.

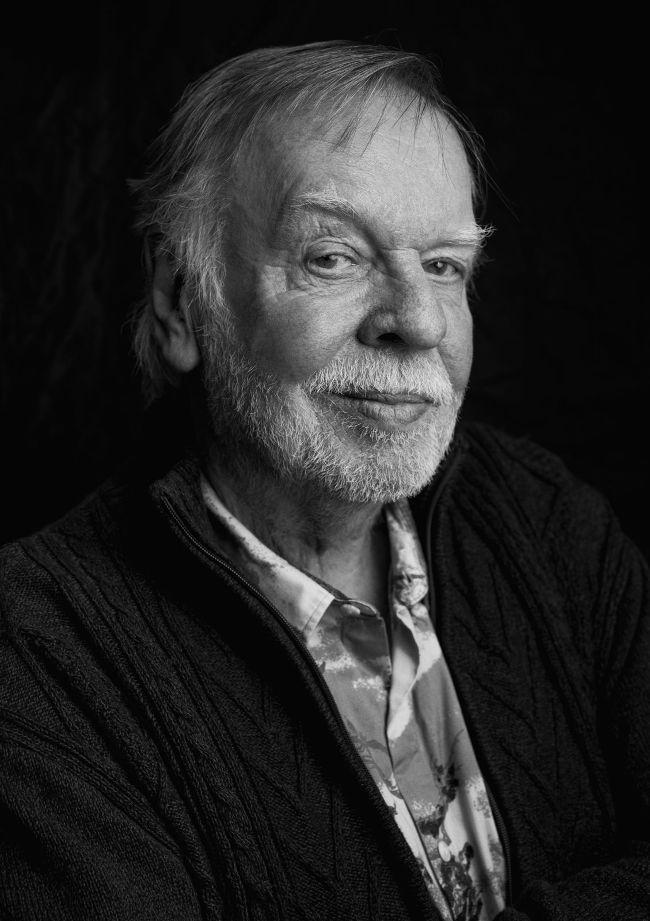

Interview by TOM DOYLE • Portrait by TOM OLDHAM

Tom Oldham, Getty

IN THE MEZZANINE SHOWROOM OF STEINWAY & Sons in London’s West End, the mellifluous sound of George Gershwin’s Summertime is wafting through the air, played by a pianist with a gift for ornate arpeggios and a distinctive touch. On this Tuesday morning, Rick Wakeman is making a brand new Model D grand piano (price tag north of £200K) absolutely sing. He pauses to marvel at the instrument’s luxurious tones, comparing it to some of the clapped-out Steinways he’s just played on his Final Solo Tour of America.

“The trouble is, a lot of hire companies don’t look after ’em,” he grimaces. “So they arrive, and you go, This is terrible.” Wakeman, 76, today wearing an orange and white Hawaiian shirt under a grey chunky knit cardigan, got back from the States three days ago and has, by his own admission, “been a zombie since”.

Nonetheless, over three hours with MOJO, he is sparky company, befitting a famed musician who in recent years has enjoyed a parallel career as a TV personality, author and raconteur. Born in 1949 in the west London suburb of Perivale, growing up in nearby Northolt with music-dabbling parents, he became a piano prodigy, then a session ace, featured on records by David Bowie, Marc Bolan, Cat Stevens and Lou Reed, along with a raft of one-hit wonders including Edison Lighthouse’s 1970 UK Number 1 Love Grows (Where My Rosemary Goes), and novelty tracks such as Oliver! actor Jack Wild’s The Pushbike Song (performing bicycle bells) in the same year. Wild also sold Wakeman his first Minimoog synthesizer, at a rock bottom 30 quid (when they cost over £1,000 new), after buying one, misunderstanding the concept of the monophonic synthesizer, and believing it to be broken.

“Jack said to my manager,” Wakeman laughs today, “‘It’s no fucking good to me if it only plays one note. Tell Rick to keep it.’”

In Yes from 1971, and with a series of high concept solo albums, Wakeman pushed the melodic possibilities of the synth, displaying a dazzling virtuosity that made him sound like a human sequencer. He also became renowned for a certain nonchalance that was at odds with prog rock seriousness, famously enjoying a curry on-stage in Manchester in 1973 during a longueur in a Yes show on their indulgent Tales From Topographic Oceans tour.

More than half a century on, there are few signs that he’s slowing down. Neither are the intricate and demanding pieces that he performs nightly on-stage. He admits however that, as the years pass, they do extract an increasing toll on his long-suffering digits. His solution is to come off-stage and immediately plunge them into buckets of iced water.

“That,” he colourfully notes, “is the equivalent to the first time you have sex. I mean, I’m my own worst enemy. I love playing. It’s all I’ve ever done since I was five. So 71 years of it, and I can’t imagine doing anything else. I will carry on playing through the pain… whatever it takes.”

Your father had been a pianist in the army, in Ted Heath’s big band. So, it was in the blood?

Well, I was born in ’49 and mum and dad, before the Second World War, they had a concert party called The Wakeans, with my Aunt Esther, Aunt Olive and Uncle Stan. But they enjoyed it so much, after the war, they used to meet in our little front room to relive the act. When I was four, I used to climb out of bed and sit on the bottom of the stairs and listen. And I thought it was absolutely wonderful. I just wanted to play.