WE HUNGER

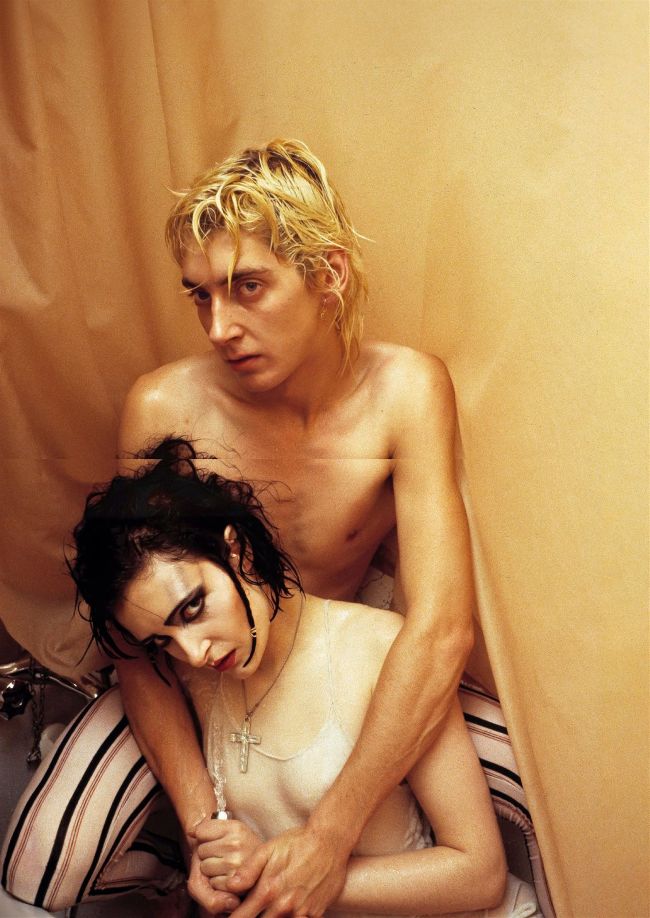

Body heat: Budgie and Siouxsie make a shower scene, Newcastle, August 1981.

Behind the darkling power of SIOUXSIE AND THE BANSHEES lay fraught relationships between troubled people-not least the lovers at its core: iconic singer SIOUXSIE SIOUX and livewire drummer PETER EDWARD CLARKE, AKA BUDGIE, In a moving and extraordinary new memoir, extracted here, Budgie delves into the relationship's incendiary ups and downs, a rag doll dance encoded the moment he first set eyes on her: "I saw her body, her stature, as a statement. Portrait: ADRIAN BOOT

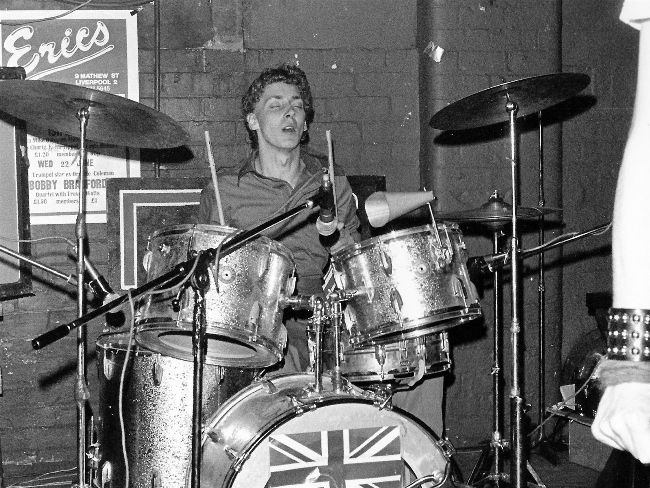

In the happy house: Spitfire Boys’ Peter ‘Budgie’ Clarke on-stage at Eric’s, Liverpool, 1977

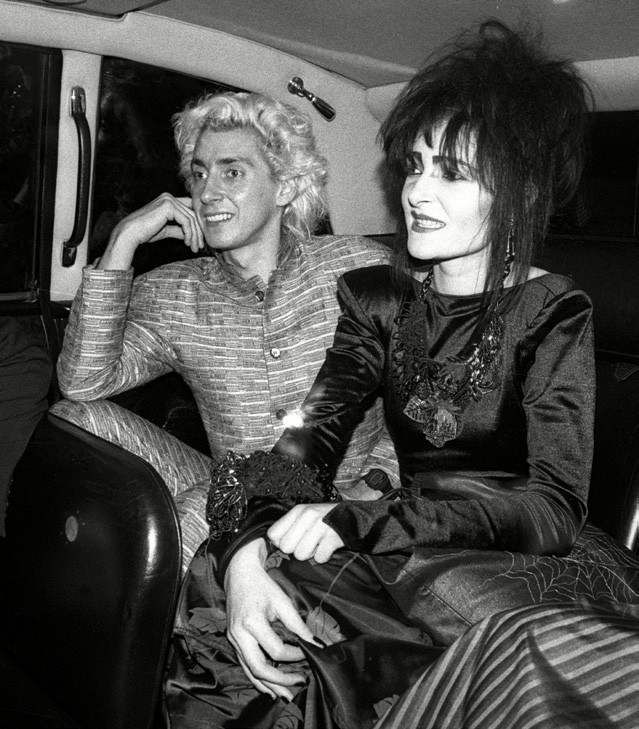

Budgie, 1985

Budgie and Siouxsie arrive at Her Majesty’s Theatre, London, for Phantom Of The Opera, October 23, 1986

pre-Budgie Banshees (from left) Steven Severin, John McKay, Kenny Morris, Siouxsie Sioux, 1978.

PETER CLARKE WAS BORN ON AUGUST 21, 1957. RAISED IN THE Merseyside town of St Helens, traumatised at 12 by his mother’s sudden death, he earned his nickname breeding budgerigars before being drawn into Liverpool’s post-punk scene, drumming with the Spitfire Boys and in Big In Japan with future Frankie Goes To Hollywood singer Holly Johnson. But first, in October 1977, there was a fateful encounter with Siouxsie And The Banshees…

Tom Sheehan, Hilary Steele, Mirrorpix, Alan Davidson/Shutterstock, Richard Haughton/Bridgeman Images, ITV/Shutterstock

SOME GUYS FROM ST HELENS KNOCKED ON MY DOOR out in Aigburth and said, “You play drums, don’t you?!” It was an accusation.

“No, I don’t. I’m a painter,” I responded.

They told me they had a support slot at Eric’s club, opening for a band called Siouxsie And The Banshees, to try and goad me into it. “Have you heard of Siouxsie And The Banshees?”

“Yeah.”

“You like The Clash?”

“Yeah.”

“And the Pistols?”

“Sure.”

“Well, we’re going to open tomorrow night at Eric’s. Are you in?”

I feigned a moment to think, then said, “OK.”

We didn’t get down to Eric’s in time to support the Banshees – in those days, you had to get in, set a drum kit up side-stage, punch somebody out who was trying to get their kit on at the same time, and whoever won got the gig.

You’d sometimes see drum kits come flying out the side door. We were not organised enough to manage it, or perhaps it had just been a trick and they’d used the allure of the Banshees to get me to join.

It was probably the first time the Banshees had played at Eric’s, and it was chaos, with a lot of broken glass around the stage. Holly Johnson was down at the front, his head shaved and tinted a pale green. He wore a string lasso around his neck with a loop on the end that he was tugging at as if to say, or threaten, “I would die for you.” Jayne Casey and Paul Rutherford always danced together. They had a skipping dance: hop, skip, hop, kick, not pogoing. Pogoing was not allowed because pogoing was just passé. It was the surest sign that you’d read and believed the wrong thing, that you were already out of date.

What I took away from that gig was how chaotic they were on-stage, how every song seemed to just disintegrate, with no ending. The drums were pounding yet musical, and the guitarist was annoying. His bright orange hair matched his guitar’s bright orange lead, which was long enough to reach to the back wall of the club. He kept running off-stage and banging into people, including me, knocking my drink flying.