The Factor

THE UNMISTAKABLE BLAST OF A .44 Magnum pierces the quiet night air of Montecito. One shot, then another, then a third – disquieting noises emanating from the California coastal residence of one Warren Zevon.

It’s autumn 1978, and Zevon is at the height of his fame, with a freshly certified gold album and a hit song still lingering on the charts. But on this night, the drink and self-loathing – and the prospect of rehab that his family have been pushing – have him looking to unload his .44 at something or someone.

The gunshots immediately wake Zevon’s wife Crystal. Terrified, she cautiously makes her way to the source of the sounds, her husband’s back house studio. She arrives and sees the long-barrelled gun at Zevon’s side, takes in his blank expression, and then glimpses the target he’s just put three big bullet holes through: it’s the image of his own face on the cover of his Excitable Boy LP.

Some 45 years after his biggest hit, and 20 years since his passing – tragically at the age of 56 from mesothelioma – Warren Zevon remains a fascinating mass of contradictions. A classically trained pianist with a rock’n’roll heart, a brilliant songwriter whose literary tastes ran the gamut from Graham Greene to Mickey Spillane, Zevon was a unique mix of brains and brawn, high art and low culture.

“Once, he opened a show for me,” recalls Jackson Browne, Zevon’s producer, champion, and close friend, “and I introduced him to the audience as ‘The Ernest Hemingway of the 12-string guitar.’ Later he corrected me and said, ‘No, no – Charles Bronson of the 12-string guitar.’”

Earlier this year, Zevon was nominated for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Though he fell short of induction, it was rare popular recognition for an artist who spent much of his life basking in critical acclaim and cult adoration but experiencing only fleeting commercial success.

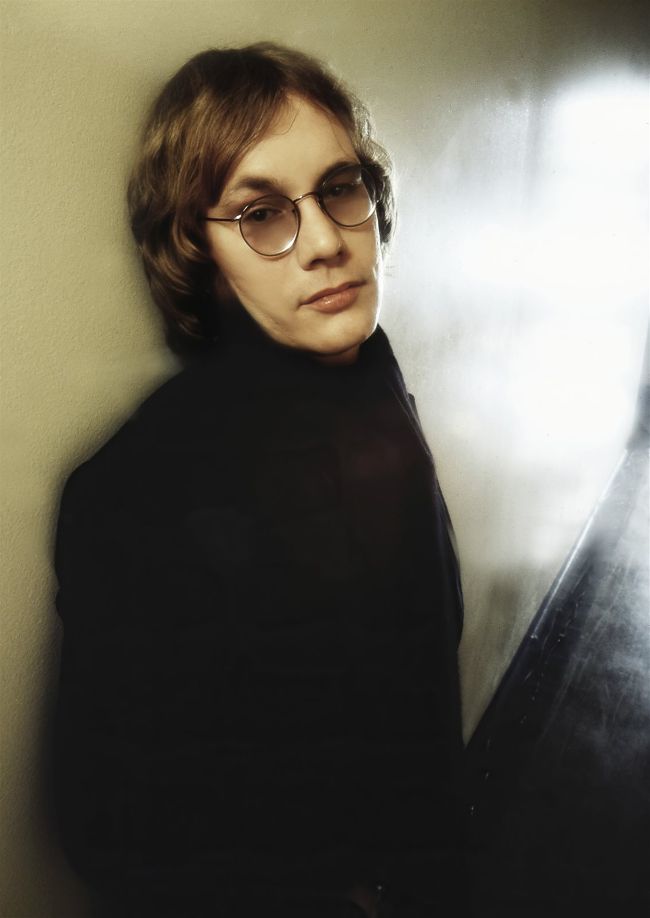

Back against the wall: Warren Zevon in 1978. “There’s so much life in his songs,” says friend and collaborator Jackson Browne.

Getty/Aaron Rapoport

“The people who heard and loved Warren’s songs all had this feeling like they were the only ones that got him,” says Browne, chuckling. “I know I thought that. I’m sure there are people who are just discovering him now who think: I’m the only one who really gets this guy.”

WARREN ZEVON’S LIFE began in Chicago, Illinois, on January 24, 1947. He was effectively born into a dichotomy: his mother was the closely guarded daughter of strict Mormons from California; his father a Ukrainian Jew from New York City, a gambler, and gangster twice her age.

Zevon’s birth had not been an easy proposition either. His mother had a congenital heart condition; she wasn’t even supposed to bear children. “Her family urged her to abort the baby, and she wouldn’t do it and she nearly died in childbirth,” says Warren’s exwife and biographer Crystal Zevon. “As a kid, whenever he would misbehave, his grandmother would say, ‘You’re killing your mother. She almost died having you.’ It was a guilt trip that was laid on him throughout his whole life.”

Though a gifted pianist as a child – he even managed to win the notice of composer Igor Stravinsky – Zevon was kicked out of his mother’s Fresno home as a teen and moved in with his father in Los Angeles. Immersing himself in blues and folk and Dylan, Zevon spent the latter half of the ’60s scuffling around the LA music biz, working as a session player and selling the occasional tune, including one – Like The Seasons – that wound up as the B-side of The Turtles’ hit Happy Together. He signed to the band’s White Whale label, playing as half of a boy/girl duo called lyme & cybelle, and later made ends meet doing commercial work, penning jingles for Gallo Wine and Chevrolet.

Zevon’s first shot at a solo career would come in 1969, under the mercurial guidance of Sunset Strip Svengali Kim Fowley. However, Zevon and Fowley fell out during the making of the LP for Imperial. The resulting Wanted Dead Or Alive was an odd, psych-flecked affair that promptly flopped. That same year, Zevon fathered a son, Jordan, with actress girlfriend Marilyn ‘Tule’ Livingston. He would later cut a second album for Imperial, this time with the help of producer Bones Howe, but the project was shelved by the label and never released.