ENTROPY ISN’T WHAT IT USED TO BE

Nate Drake provides a brief history of randomness in Linux and how the kernel uses it to keep your data safe.

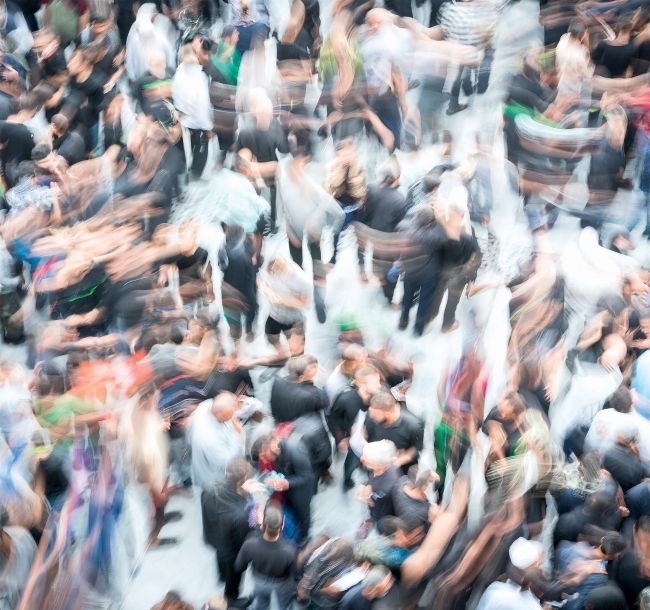

CREDIT: Jasmin Merdan/Moment/Getty Images

As a Linux user, if you’ve ever visited a site secured by SSL, securely wiped a drive or digitally signed an email, you’ve made use of the Linux kernel’s built-in RNG (random number generator). It works by collecting entropy (disorder) from various sources, such as hardware RNGs, interrupts and CPU-based ‘jitterentropy’. This entropy is extracted using a secure hash function and used to seed a set of cryptographic random number generators (CRNGs). As long as the kernel’s running, entropy continues to be collected and the CRNGs are therefore reseeded with high-quality random bits. The bits generated by the kernel’s RNG are technically pseudo-random. This is comparable to someone rolling a die many times and writing down the results. Whenever you ask for a die roll number, you get the next on a predetermined list.

Pseudo-random number generators, or PRNGs, are systems that are efficient in reliably producing lots of artificial random bits from a few true random bits. For example, a true RNG that relied on keypresses would stop generating randomness as soon as the user stops using the keyboard. However, a PRNG would use these random bits of initial entropy and then continue producing random numbers.

Any predictability in supposedly random data is bad news for cryptography. The very basis of generating session keys to secure the SSL connection between your browser and a website is that these keys can’t be reverse engineered at a later date. In this guide, you’ll explore the nature of entropy further and discover how Linux still provides one of the best guarantees for securing your data.

In 1984, a 35-year-old former ice cream van driver called Michael Larson flew to California to take part in the hit TV show Press Your Luck.

Players took virtual ‘spins’ on a large electronic grid of boxes, using lights that flashed seemingly randomly to show whether they’d won thousands of dollars in cash, fabulous prizes and yet more spins. Crucially, the squares also included Whammies, which if landed on caused players to lose all their money. While players could win a few thousand dollars through careful play, every spin meant a one in six chance of losing all their winnings, leaving the host free to commiserate then cut to commercial.

But Larson had a trick up his sleeve. Back home he’d wired up a series of VCRs to play back episodes of Press Your Luck for up to 18 hours a day. This is how he discovered that far from being random, the board used six predictable patterns.