It’s probably not one of your favourite languages, but Mike Bedford says if you want to learn about programming’s heritage, don’t ignore FOCAL.

It’s probably not one of your favourite languages, but Mike Bedford says if you want to learn about programming’s heritage, don’t ignore FOCAL.

Credit

: https://github.com/AndrewSav/focal-69

OUR EXPERT

Mike Bedford

has used several

languages and dabbled in many more. Now he can add FOCAL to that list, and this experience has persuaded him of its place in history, in a curious sort of way.

The PDP-8 was, perhaps, DEC’s first successful minicomputer. Cheap it wasn’t, despite it costing vastly less than mainframes, but at least it could run FOCAL.

On early versions of FOCAL, the only option for saving your program was to use the paper tape punch on a teletype terminal.

If you’re an Ubuntu user, there’s a pretty good chance that the word “focal” will bring to mind Focal Fossa, the code name of the Ubuntu 20.04 LTS release. But that’s not our subject here. Instead, we’re delving into a programming language that goes by the name of Formulating On-line Calculations in Algebraic Language (alternatively, FOrmula CALculator, according to some sources), or FOCAL for short. As we shall see, FOCAL is no spring chicken, which is quite appropriate for this, the latest instalment of our series on classic languages, by which we mean old.

FOCAL first saw the light of day all the way back in 1968, when it was introduced by Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) for the company’s range of PDP-8 minicomputers, in those pre-personal computer days. It was intended as a simple beginners’ language and, as we’ll see, with just a handful of instructions, it must surely be one of the simplest languages ever devised. You might wonder, given that BASIC, which had appeared four years earlier and had the same philosophy, wasn’t DEC’s beginners’ language of choice, and perhaps it should have been. DEC went on to release FOCAL on its newer and hugely popular PDP-11 minicomputers, which launched in 1970, but it was quickly surpassed on that platform by BASIC, and was soon heading for obscurity. Perhaps the only other platform on which FOCAL made an appearance, back in those days of yore, was the 1974 Altair 8800 microcomputer, which we featured in LXF278 as part of our series on emulating historic computers. Needless to say, though, FOCAL hasn’t escaped the attention of those intent on

preserving our heritage, and is now freely available both for Linux and online.

Tackle the FOCAL

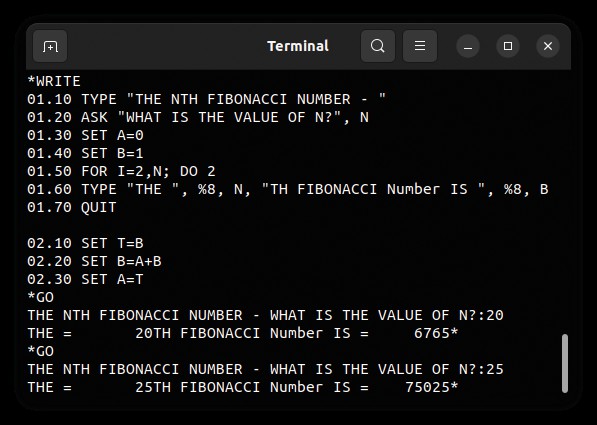

Before getting to grips with the language, we’re sure that you will want to try it out as you go, so to start we’ll recommend a couple of FOCAL implementations. You can find FOCAL-69, which was a slightly enhanced version of DEC’s original FOCAL, albeit not as updated as FOCAL-71, which notably added file support, at

https://github.com/AndrewSav/focal-69

. You have to build it yourself from source code, but that’s simple.

Like the original BASIC, FOCAL was an interpreted language, which included its own IDE, although it was very different from what most people would think of as an IDE today. This was due, in no small part, to the fact that FOCAL would mostly have been run on a hardcopy terminal such as a teletype, instead of a display screen. Under Linux, it runs in a terminal window, which is as close as most of us can get to using a teletype terminal. Instructions can either be entered without a line number, in which case they are executed immediately, or with a line number, in which case they’re stored as part of a program for subsequent execution. See later for more information on line numbers – they’re probably not what you’d expect. To change a line in the program, re-enter it with the same

line number. To delete that line, type ERASE followed by the line number. Alternatively, you can delete all the steps in a group by typing ERASE , followed by the group number, or delete the entire program with ERASE ALL . To check your code, having made alterations, type WRITE and the full program is listed. Similarly, you can see a single line by typing WRITE followed by the line number, or all the steps in a group by typing WRITE followed by the group number. When you’re happy with your program, type GO to execute it from the start, or GO followed by a line number to start execution from the specified line.

Note that this early version of FOCAL has no instructions for saving and loading programs to or from disk. This didn’t mean that programs couldn’t be saved and reloaded, though, because teletype terminals often had built-in paper tape devices. So, if you turned on the paper tape device before executing a WRITE command, you’d end up with the code punched on paper tape. Similarly, if you used the paper tape device to read a tape on to which you’d already saved a program, the result would be just the same as if you’d typed the code manually. We don’t expect many of you are using a teletype on your PC, though, so we recommend transferring your code between the terminal window and a text file using copy and paste in the usual way, while remembering that FOCAL users of old couldn’t have done that. For more details of the IDE, take a look at DEC’s FOCAL Programming Manual, which you can access at

https://bit.ly/lxf301focal.

If you want an even quicker way to try your hand at FOCAL programming, take a look at

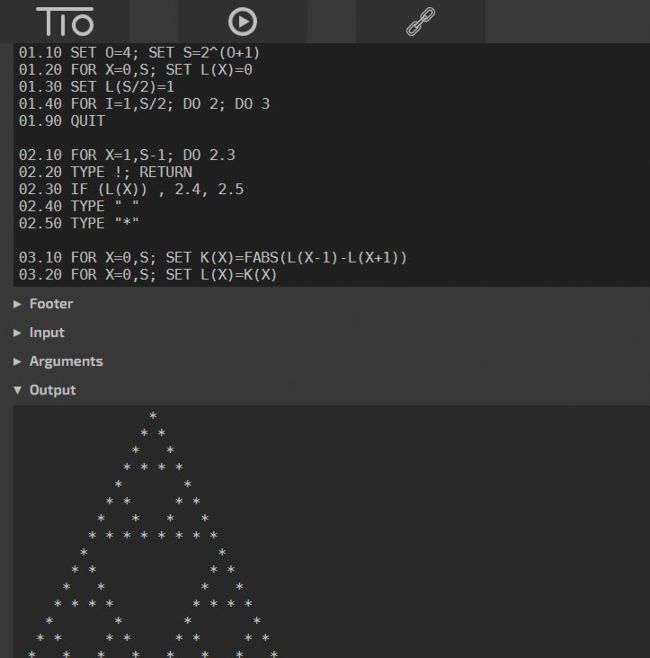

https://tio.run

(Try It Online), which offers FOCAL-69 among its 680 languages. Despite it providing a hassle-free solution, it doesn’t fully replicate the original FOCAL experience as it doesn’t implement the complete programming environment that you get with the GitHub Linux version. Instead, you use TIO’s common interface for entering and editing your code. Furthermore, in our experience, the ASK statement doesn’t seem to work, and we encountered other glitches.

Language overview

In terms of the number of instructions in FOCAL, we’d say that it’s approximately the same as the original Dartmouth BASIC. It’s difficult to be more specific because some of the instructions are rarely used in a program, as they’re really intended for editing and executing a program, even though you’re not prevented from including them in a program. For example, although you can include a WRITE instruction in a program, we suggest that writing a program that generates a listing of itself isn’t especially useful. Similarly, you could include an ERASE ALL instruction, even though a program that deletes itself part way through would be little short of disastrous. Useful or not as part of a program, though, the original FOCAL had 15 instructions, which really isn’t a lot.

As we’ve already seen, FOCAL commands can be executed immediately by entering them without a line number, or stored as a program for execution later if they’re preceded by a line number. Line numbers comprise a group number and a step number, separated by a dot, and must be in the range 1.01 to 15.99. Groups and step numbers in the range 1 to 9 can be entered without or without leading zeros, although even if you omit them, FOCAL shows the line number with leading zeros added when you list the program. While bearing in mind that FOCAL was supposed to be a beginners’ language, the range of available line numbers might suggest an unusually low limit on the number of lines in a program. However, this can be alleviated by putting several instructions, separated by semicolons, on the same line.

Each of FOCAL’s keywords starts with a different letter, and this allows them to be entered as just that initial letter. So, for example, instead of the instruction TYPE N you could use T N but we would argue that while this offers a modest saving in the time taken to enter your code, it doesn’t exactly do wonders for readability. So, with that word of introduction, here are FOCAL’s instructions in alphabetic order: ASK , COMMENT/CONTINUE (essentially the same in that they do nothing, except that COMMENT usually

precedes some descriptive text), DO , ERASE , FOR , GO/GOTO (exactly the same except that GO is usually an immediate command to execute a program, while GOTO , which would be followed by a line number, transfers execution to that line), IF , MODIFY , QUIT , RETURN , SET , TYPE and WRITE .

Forget about coloured syntax highlighting – coding in FOCAL-69 is definitely an old-school experience, so you might as well configure your terminal window to white text on black.

We’re about to look at some of those in more detail, but a couple of introductory comments are necessary. First, we need to explain how FOCAL interprets arithmetic expressions. The main point is that the precedence of operators is ^ (exponentiation), * (multiplication), / (division), + (addition), - (subtraction). This differs from most other languages in which multiplication and division have the same precedence, as do addition and multiplication, and operators with the same precedence are executed left to right. This means, for example, that 10-5+2 would be evaluated as 3 in FOCAL, not 7 as it would be in other languages. Brackets can be used to override the default precedences although, atypically, these can be (), [] or <>, so long as they’re properly matched. And second, we should point out that variable names can be either one or two letters, or a letter followed by a figure. All variables can be treated as arrays – A(1) , for example – without specifically being declared as such.

The SET instruction is used extensively, so it’s a good place to start. You know, no doubt, that in most languages, assigning a value to a variable doesn’t require a keyword, so the instruction would commonly be something like X = 1 or, in some earlier languages, X := 1 . FOCAL differs from common practice in this respect in requiring the SET command, so assigning a value of 1 to the variable X would involve SET X = 1 . It’s interesting to note that, although later versions of BASIC allowed assignments to use the familiar X = 1 type statement, the original Dartmouth BASIC required the LET keyword, which is a direct parallel to FOCAL’s

SET . This is just one instance in which FOCAL statements differed from the BASIC equivalent only in the keyword, apparently for no good reason except to confuse BASIC users. However, some other instructions were quite different, as we’re about to see.

Next up is the IF statement, and this is probably quite different from what you’re used to, because FOCAL doesn’t have the usual relational operators such as equal, greater, less than and so on. In fact, FOCAL’s IF statement has more than a little in common with a processor’s underlying instructions, and hence assembler programming. This seems rather strange for a beginners’ language, especially when we bear in mind that BASIC and other popular languages that preceded FOCAL, such as FORTRAN and Algol, did have relational operators. FOCAL’s IF statement includes a variable name or arithmetic expression, which must be enclosed in round brackets, followed by three line numbers representing where execution continues if the expression gives a negative, zero or positive result respectively. As an example, IF (N-5) 01.20, 01.30, 01.40 causes N-5 to be evaluated and then, if the result is negative, the program branches to line 01.20; if it’s zero, it branches to 01.30; and if it’s positive, it branches to 01.40. Actually, it’s not necessary to provide all three line numbers – so, for example, if you don’t want it to test for a negative result, you could use the statement IF (X) , 01.30, 01.40 .

Let the FOCAL flow

The execution of subroutines is another rather unusual aspect of FOCAL, and certainly different from that of early forms of BASIC. Subroutines are executed using the DO instruction, which can take two forms. If DO is followed by a complete line number (such as DO 2.5 ), then the specified line is executed, after which execution continues with the line after the DO command. So, in this case, the subroutine is just a single line long, although that line can have several

instructions, separated by semicolons. If DO is followed by a group number – the part of a line number before the dot – (such as DO 3 ), all lines in that group are executed before transferring control to the line following the DO statement. Alternatively, if a

RETURN instruction is encountered in the group, execution of the subroutine terminates, again transferring instruction to the line after the DO statement. Note that nothing specifically defines lines or groups as subroutines, so if such code is encountered, other than via a DO instruction, it is executed. Generally, you’ll want to prevent that.

We did find a few issues with the FOCAL implementation at

Try It Online, but you might want to give it a go for your very first steps with this archaic languag

e.

FOR loops are also a bit different from the way they’re usually implemented in that the looped code can only be a single line long, as in the following example: FOR N=1,10; TYPE N . However, that line can include more than one instruction separated by semicolons, or the FOR instruction could be followed by a DO statement. Note also that, while the above example increments N in steps of 1, if there are three numbers, such as FOR N=1,0.5,10; TYPE N , the variable is incremented by the middle number which, in this case, is 0.5.

The final thing we’ll mention in this brief overview, before looking at a complete program, concerns FOCAL’s textual data features. The most common use of text is a quoted text string in a TYPE instruction or an ASK instruction, such as TYPE “HELLO WORLD” or ASK “WHAT IS YOUR AGE?”, A . Other than that, though, support is limited in the extreme. If an attempt is made to assign text to a variable – and using an

ASK instruction to get a yes or no input from the user is one of the few good reasons to do that – a number representing the character(s) typed is assigned to the variable. Normally this is a single-character response, in which A=1, B=2 and so on, though we notice that up to three characters can be entered. In that case, for example, ABA would return a value of 121.

Sample program

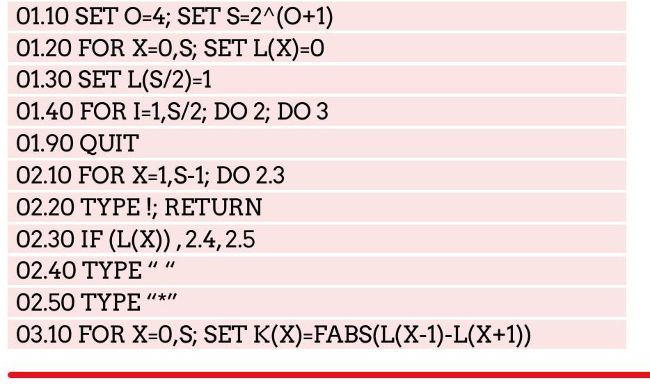

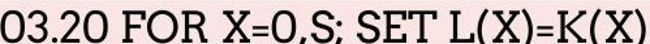

So far, we’ve only looked at single instructions, so it’s surely a good time to start putting some of them together to create a program. Here’s one you might like to try, before turning your attention to writing your own code from scratch. The code was found in Rosetta Code (https://rosettacode.org), although we converted the single-letter instructions to their full keywords to make it easier to read. Its purpose is to draw a Sierpinski triangle, but if you’re not familiar with that, you can see from the screenshot of Try It Online (above-left) what it looks like.

You’ll notice some things here that we glossed over in our whistle-stop tour of the language. We didn’t actually say anything about the TYPE instruction, for instance; indeed, it can be fairly intuitive, with the following statement being fairly typical: TYPE “HERE ARE THE ANSWERS “, X, Y, Z . However, by default, TYPE doesn’t throw a new line, and to do that, you need to add ! at the end of a TYPE statement, which need not have anything before the ! , as you can see in line 02.20. Also, although not relevant to this code, you should know that FOCAL’s default way of formatting a numerical value is eight digits before a decimal point and four afterwards. So, for example, if you use TYPE 1 to display the value 1, it is shown as

1.0000 . This can be overridden by supplying the number format – so, for example, TYPE %4.0, 1 specifies four digits before the decimal point and none after, so it displays 1 .

Something else we’ve not seen before is the FABS function, which appears in line 03.10, and which returns the absolute value of its argument. The other available functions are FSQT , FSGN , FITR , FRAN , FEXP , FSIN , FCOS , FATN and FLOG , and these return the square root, sign (-1 for a negative number, +1 for a positive number or zero), integer part, random number, exponential, sine, cosine, arc tangent and natural logarithm, respectively.

We’re most definitely of the view that doing is the best way of learning, so that’s our excuse for drawing a line under our exposé of FOCAL at this point, and suggesting, as our parting shot, that you now try out some coding of your own.

The 1974 Altair 8800, arguably the first ever personal computer, provided a vehicle for FOCAL’s swan song.

QUICK TIP

We’ve only seen FOCAL displaying textual results, although there are two functions for graphical display. To use those, though, some additional hardware was needed in the form of a so-called oscilloscope display, which we can think of as an analogue graphics terminal.

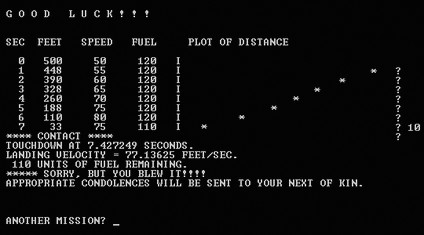

The original Lunar Lander was a text game developed in FOCAL by Jim Storer in 1969.

LET US HELP YOU STAY FOCAL…

Subscribe now at

http://bit.ly/LinuxFormat

QUICK TIP

Our theme here is specifically the FOCAL language, and not the DEC PDP-8 minicomputer more generally. However, if we’ve inspired you to delve into the latter, there are several emulators available for you to try out.

INVESTIGATING THE DEC PDP-8

The early to mid-’60s was the era of the mainframe but things were changing. In 1965, DEC launched its PDP-8 minicomputer. Costing less than $20,000 (which had an equivalent spending power of $360,000 today), compared to millions for a mainframe, it brought computing to much smaller organisations than previously.

The first PDP-8s had a memory capacity of 4K 12-bit words, which equates to 6KB, or 0.006MB or 0.000006GB. Given the minuscule figures, we assume that the rationale of each of FOCAL’s keywords having a unique initial letter wasn’t just to allow programmers to enter just that letter. It’s our guess that only that initial letter was stored, reducing the amount of space a program would occupy.

It’ll come as no surprise that the memory capacity wasn’t the only aspect in which a PDP-8 was vastly under-powered compared to today’s PCs. Turning to the clock speed, we find a pedestrian 666kHz for the initial offering, and a memory access speed of 2.3µS. What’s more, that unusual 12-bit word length almost takes us back to the eight bits of pre-1978 microprocessors, a far cry from today’s 64 bits. The upshot of all this is that PDP-8 emulators running on a PC – some of which include FOCAL – run much faster than on a real PDP-8, despite the not-insignificant emulation overhead.

QUICK TIP

Instead of editing a line of code by retyping it, FOCAL’s MODIFY command enables you to edit a line. Because FOCAL would generally have been run on a hardcopy terminal, though, this was nothing like editing code in a modern IDE. You’d move to a point in the line by searching for a character, and then edit it using various key combinations.

FOCAL’S CLOSEST RELATIVE

We’re familiar with the idea of programming languages being influenced by an earlier language, and FOCAL is no exception. Its predecessor was called JOSS, which stands for JOHNNIAC Open Shop System. JOHNNIAC was a computer produced by RAND Corporation on which it was first implemented, and we haven’t got a clue about the Open Shop bit. What we can say is that it was one of the first interactive, multiuser programming systems and associated language, being released in 1963.

Like Dartmouth BASIC and the now familiar FOCAL, JOSS could be used either as a high performance calculator by entering commands without line numbers, or for creating a program by adding line numbers. Those line numbers were used both to determine the sequence of instructions in the program and as the destination of the TO instruction (the equivalent of GOTO ) and subroutine calls.

It seems odd that JOSS’s IF clause (not a statement in its own right, because IF was used as a conditional part of another statement, such as TYPE N IF N>=0 ), could use relational operators. Our reason for suggesting that’s surprising is that FOCAL didn’t follow JOSS in this respect, nor the likes of contemporary languages such as FORTRAN or BASIC, even though the FOCAL solution was, arguably, inferior, at least for beginners.