Life, books and arts

Present imperfect

Homeschooling parents are discovering how much time in class is taken up with educational jargon. When did the National Curriculum become so rigid?

ELIANE GLASER

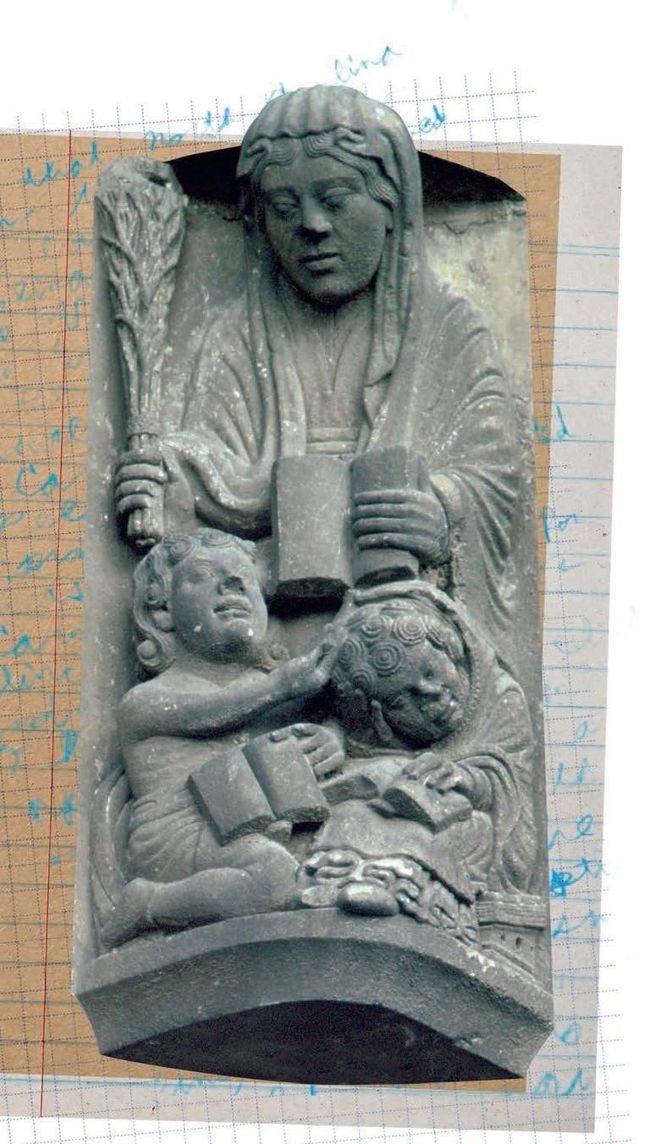

Previous page: A carving from Chartres Cathedral shows Dame Grammar threatening to beat her pupils with a bunch of twigs

In normal times, my cheery “So, how was school?” rarely receives more than a grunted “OK.” But homeschooling is revealing what my children actually do all day. And the discovery has come as a shock.

My 11-year-old son and eight-year-old daughter go to a perfectly decent state primary, which has valiantly provided worksheets week by week throughout our successive lockdowns. But I read them with incredulity, hilarity-and horror.

My daughter is told to improve her writing using “PUGS (Punctuation, Up-levelling, Grammar and Spelling).” (“Up-levelling,” I gather, means “improving.”) Meanwhile, she is left finding comprehension incomprehensible: “Use evidence from the text to justify your thinking!”-the exclamation mark failing to animate the task, which involves describing the appearance and personality of protagonists; or spotting expanded noun phrases. (I kid you not.)

Suspicious, I took out their old exercise books, which I’d shamefully only ever briefly glanced at in the holidays. At the top of each page is an “LI,” which, they informed me after some racking of brains, stands for “learning intention.” (Other schools use “learning objectives” or “WALT”

We Are Learning To…). When she was six and seven, my daughter was in the habit of writing her name followed by a row of hearts and kisses. Yet under that charming heading, she’d been made to scrawl such heart-sinking formulas as “LI: to practise inference skills”; “LI: to interpret a pictogram”; “LI: to work systematically to solve a problem”; and “LI: to identify features of a non-chronological report.”

Underneath the “LI” they have to paste in a checklist of “success criteria”: “I can add extra information to my sentence using a subordinate conjunction”; “I can use time adverbials”; “I can include technical vocabulary.” It was as if I’d booked a babysitter but a marketing manager had turned up instead.

The maths worksheets seemed more cogent, but the language was just as weirdly abstract-all tell, no show. “LI: to add using expanded column method”; “LI: to use inverse relationships to solve problems”; “Challenge: how many different division facts will you be able to write for the following statements? Explain your answer.” The wording reminded me of a poorly translated instruction manual.

When Michael Gove instituted a new national curriculum in 2014, the highly technical grammar foisted on primary pupils attracted some consternation (the secondary grammar curriculum is tiny by comparison). Six- and seven-yearolds are now expected to know prepositions, conjunctions and subordinate clauses; eight- and nine-year-olds, noun phrases expanded by the addition of modifying adjectives, preposition phrases, fronted adverbials and determiners; nine- and 10-year-olds, modal verbs and relative pronoun cohesion. I don’t even know what some of these terms mean, and I’ve got a PhD in English.

Leggete l'articolo completo e molti altri in questo numero di

Prospect Magazine

Opzioni di acquisto di seguito

Se il problema è vostro,

Accesso

per leggere subito l'articolo completo.

Singolo numero digitale

April 2021

Questo numero e altri numeri arretrati non sono inclusi in un nuovo

abbonamento. Gli abbonamenti comprendono l'ultimo numero regolare e i nuovi numeri pubblicati durante l'abbonamento.

Prospect Magazine