EMULATION

Experience the EDSAC

Credit: www.dcs.warwick.ac.uk/~edsac

EDSAC was the first machine to provide a regular computing service. Mike Bedford explains its quirks through emulation.

OUR EXPERT

Mike Bedford considers himself fortunate to have never had to program EDSAC for real. He was almost at the point of pulling his hair out, trying to get his own code to work on the EDSAC emulator.

QUICK TIP

EDSAC came online at pretty much the same time as the Manchester Mark I, but being the first two practical stored-program computers wasn’t the only thing they had in common. Just as EDSAC morphed into LEO, the Manchester Mark I also became the basis of a commercial computer – the world’s first – in the form of the Ferranti Mark I.

The identity of the first ever computer, as we now understand the term, is well known among computer enthusiasts. That computer is the SSEM – the Small-Scale Experimental Machine – otherwise known as the Manchester Baby.

However, it was never intended as a tool to carry out practical tasks. It soon morphed into the Manchester Mark I, which was indeed intended to provide a practical service. And this brings us to our subject here. Designed pretty much in parallel, but running its first program a month later in May 1949, was the University of Cambridge’s EDSAC. Despite being a month later than the Manchester Mark I, EDSAC is acknowledged as the first ever practical, universal, stored-program computer to provide a regular computing service.

Here we’re going to investigate EDSAC, delving into its specification and its unique form of memory, and see how it influenced early computing. And should you wish to get your hands dirty, we present a practical option. As with many of our exposés of historical computers, we’ll suggest how you could get a feel for this influential machine via emulation. You could even try your hand at programming it, using an instruction set containing 18 instructions, a major improvement on the SSEM’s six.

EDSAC overview

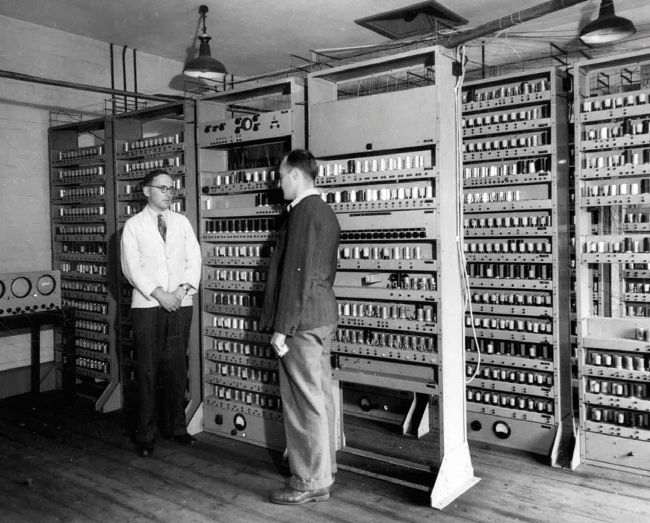

Maurice Wilkes and Bill Renwick in front of the completed EDSAC.

CREDIT:

https://commons.wikimedia.org, Computer Laboratory, University of Cambridge. Reproduced by permission.

We ought to start by spelling out EDSAC, and it transpires that those letters stand for Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Calculator. The mnemonic is really quite descriptive, even though you’ll have to wait to learn a bit more about the delay storage part.

First of all, some facts and figures that will be more understandable. As is invariably the case with ancient computers, these figures paint a picture of an almost unbelievably basic machine. EDSAC clocked up 666 instructions per second but just 166 for multiplications, memory was 512 18-bit words ( just over 1KB), input was from paper tape, and output was to a teletype.

EDSAC’S LEGACY

EDSAC made its own claim to fame in being the first practical, universal, stored-program computer to provide a regular computing service. However, its legacy is probably even greater, and this brings us to another first from the early days of computing. It might have been envisaged as a tool for scientific applications, but EDSAC drew the interest of a company with a very different application in mind. J Lyons & Co, a British food manufacturer, also operated a chain of tea shops, and its interest was in a technology that could streamline its business, an application that required large amounts of data to be handled, but which needed little in the way of complicated calculations. Recognising that computers could provide a solution, Lyons provided some funding for EDSAC in return for the rights to use aspects of the EDSAC design in its own in-house computer. That computer was called LEO – Lyons Electronic Office – and it became the world’s first computer to be used for business applications.

The computer department soon became a separate company -LEO Computers Ltd – and would go on to produce LEO II and LEO III, the latter abandoning valves in favour of transistors. Around 100 were sold – not bad for a bakery company. LEO Computers was eventually sold to English Electric, which, following several mergers and takeovers, became ICL.