NOW I FIND I'VE CHANGED MY MIND

SIXTY YEARS AGO, THE BEATLES OPENED UP THE DOOR TO A BRAVE NEW WORLD. ANIMATED BY WEED AND ACID, THEY FOUND THE INTROSPECTIVE SONGS OF HELPI, THE KNOCK ABOUT MOVIE THAT WAS ALSO A SKEWED, STONED SATIRE ON BEATLEMANIA. AND YET, AMID FRESH MADHESS AND MBES, THE ESSENCE OF 196S WAS ALSO A RETURN TO THE BAND'S ORIGINAL SOURCE, THE REVENGE OF THE BEATNIK BEATLES...

WORDS: JOHN HARRIS

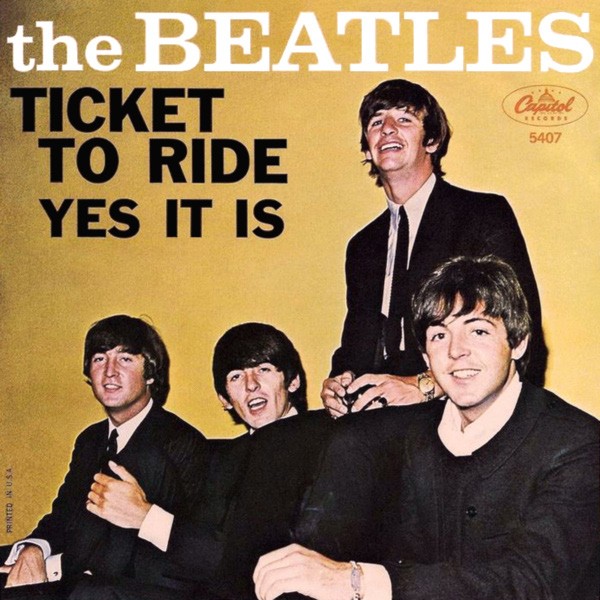

Save our souls: The Beatles’ original 1965

Help!

album cover portraits by Robert Freeman.

Apple Corps Ltd. (4)

AUGUST 15, 1965. FIRST, THERE WAS A LIMOUSINE RIDE, from the Warwick Hotel in midtown Manhattan to the East River Heliport. Then, as The Beatles were helicoptered towards Queens, they caught sight of what they were heading into. With Brian Epstein and their close aide and road manager Neil Aspinall, the four of them stared down at the 55,600 people gathered at Shea Stadium – midway through a supporting bill that included King Curtis, Brenda Holloway, and The Young Rascals.

Their pilot, George Harrison later recalled, “started zooming round the stadium, saying, ‘Look at that, isn’t it great?’” And in response, The Beatles boggled at what was about to happen: the first-ever music event in such a giant space. In the footage shot on-board the helicopter, as they silently peer down, you can sense their mixture of amazement and nerves. “It was very big and very strange,” said Ringo Starr.

Dressed in the beige military-style jackets that quickly became yet another item of Beatles iconography, they played for their usual 30 minutes, starting with a truncated rendition of Twist And Shout. The end came with Paul McCartney’s Little Richard tribute I’m Down, during which John Lennon crashed his elbow down the keys of an electric organ, and he and Harrison collapsed in hysterical giggles. Vox had made them special amplifiers, with a titanic 100 watts of sound designed to be heard above the din of the fans, but bound to do nothing of the sort. So, there The Beatles stood, soaking up the surreal atmosphere created by a crowd who seemed completely unhinged.

What is sometimes lost in accounts of the Shea Stadium concert is the equally febrile state of the country in which it occurred. The night the show took place, the Los Angeles suburb of Watts was in the midst of a six-day riot. Meanwhile, as President Lyndon Johnson doubled the numbers of young men being conscripted to fight in Vietnam, demonstrations took place at the Pentagon and the White House. At Berkeley University, students had started to publicly burn their draft cards.

Inevitably, the best music channelled a sense of flux. Less than a month before Shea, Bob Dylan had released Like A Rolling Stone, then triggered uproar by playing with an electric band at the Newport Folk Festival. American radio was still blasting out (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction, The Rolling Stones’ mewl of disdain for just about everything society had to offer. But from California, there came the very different sound exemplified by The Byrds’ version of Mr Tambourine Man: a fusion of Dylan and The Beatles which gave off not just the scent of marijuana smoke, but the sense of new substances and pleasures of an even more transcendent kind. Here, it seemed, was another kind of answer to the straight world and its excesses: not a disaffected snarl, but the impulse to turn on, tune in, and drop out.

ZUMA Press, Inc./Alamy (2), Bettmann Archive/Getty (2), Keystone Press/Alamy, Michael Ochs Archives/Getty, Jeff Hochberg/Getty

Oscar Abolafia/TPLP/Getty

What we now know as the counterculture was taking shape. And as they sprinted around America, the company The Beatles kept seemed to flip between the old and new. In Los Angeles, they finally met Elvis, and attended a party thrown by Capitol Records where the invitees included Groucho Marx, Rock Hudson and

Dean Martin. But the company they really hankered after was obvious: in the same city, The Byrds’ Roger McGuinn and David Crosby dropped by their rented house in Beverly Hills, and took LSD with Lennon, Harrison, Starr and the actor Peter Fonda. By the evening, Paul and George were hanging out at the recording session that would produce the same band’s version of The Times They Are A-Changin’.

By the standards of most of their peers, The Byrds were at the cutting edge, but presumably well aware that their visitors from England were still well ahead. After all, just as the summer of 1965 had started, The Beatles had released a single built from a droning, bass-heavy arrangement and air of bleary-eyed detachment that fitted the growing countercultural mood, but also pointed somewhere even newer. Ticket To Ride, which they played at Shea, was the first Beatles single whose length surpassed three minutes. It showed that one of their key talents was reaching new heights: as a matter of instinct, they knew exactly what time it was.

"WE GOT MORE AND MORE FREE TO GET INTO OURSELVES: OUR STUDENT SELVES RATHER THAN 'WE MUST PLEASE THE GIRLS, AND MAKE MONEY."

PAUL MCCARTNEY

IN THE MORE CRUDE UNDERSTANDING of The Beatles’ career, their move away from straight-ahead pop music and old-school showbiz decisively begins with the recording of Rubber Soul, in October 1965. The truth, however, is that a newly experimental, transcendent mindset had first begun to blossom a year before, commencing 12 months of innovation that, even though every aspect of The Beatles’ story has now been deconstructed and analysed in absurdly fine detail, still feels strangely overlooked.

A whole different ball game: (above) absolute scenes in-air and on-stage as The Beatles land in New York to play Shea Stadium, August 15, 1965, also featuring support act Brenda Holloway (centre) and manager Brian Epstein (bottom right).