BETWEEN TWO WORLDS

IN 1982 TOM PETTY WAS A STAR AND THE HEARTBREAKERS ONE OF THE HOTTEST BANDS AROUND. BUT FAME, DRUGS, DOUBT AND INTERNAL DIVISIONS WERE TAKING A TOLL. IN 2024 A REISSUE OF LONG AFTER DARK AND A LONG-LOST CAMERON CROWE DOCUMENTARY REVEAL A GROUP WALKING A TIGHTROPE, THRASHING AROUND FOR WAYS TO SURVIVE, LET ALONE SUCCEED. "THERE WAS A LOT OF CRUELTY IN THE ROOM SOMETIMES, UNNECESSARILY," THEY TELL GRAYSON HAVER CURRIN.

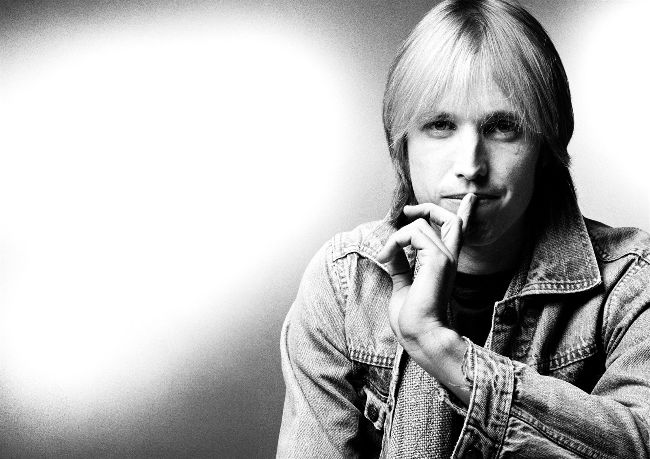

Lucky man: Tom Petty in an outtake from the Long After Dark album cover shoot, 1982.

PORTRAIT BY DREW SACKHEIM

STAN LYNCH WAS ON THE BEACH IN Santa Monica when he realised his life had changed, that his adolescent rock star dreams were suddenly real.

Lynch and another drummer friend, Robert Williams, had been jogging down the California shoreline when they heard one of Lynch’s drum breaks blasting from a transistor radio. Tickled, they stopped to listen. That’s when the duo noticed that three nearby radios were each playing separate singles from Damn The Torpedoes, the third album by Lynch’s band, Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers: Refugee, Here Comes My

Girl, Don’t Do Me Like That. In the dawning days of 1980, this wasn’t a blip; this was a phenomenon.

“I’m from fuckin’ Florida, and the last thing I remember, I’m playing in a titty bar for 50 bucks a week,” a grinning Lynch tells MOJO from the same Florida house he bought later that year. “Now I’m in a famous rock band, I guess? We’re like a sauce, and the world is marinating in this shit.”

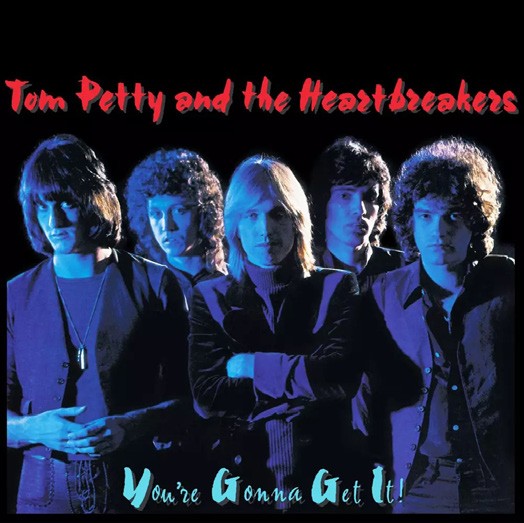

Just three years earlier, the Heartbreakers’ rock’n’roll ambitions had seemed stillborn. Their self-titled 1976 debut had sold only a few thousand copies Stateside when the band opened for Nils Lofgren in the UK in May 1977 and positive British press grew momentum. With Mike Campbell’s serrated riff cutting beneath Petty’s sneer, Breakdown had become a tardy hit, helping propel the Heartbreakers’ follow-up album, You’re Gonna Get It!, to the charts only months later.

That record, though, was but a minor prelude to Damn The Torpedoes, financed by Neil Young/Joni Mitchell manager Elliot Roberts and fixated over by producer Jimmy Iovine as Petty wrestled his way out of the record contract that had drawn him from the Sunshine State to the Golden one. The Heartbreakers quickly became one of the country’s biggest bands, the hitmakers at the crossroads of old-fashioned rock and the burgeoning new wave.

Indeed, just weeks after that beachside epiphany, Lynch remembers leaving LA’s The Forum in a limousine next to Roberts, who blew smoke from a joint he’d just rolled into the drummer’s face. The Heartbreakers had just played their first show there, and the car was bound for an afterparty at the Whisky A Go Go. Lynch asked Roberts if they needed to let anyone know they were on their way, so they wouldn’t have trouble getting past the crowds. Roberts just laughed.

“Elliot goes, ‘Crosby, Stills & Nash would give their left nut to be hot, but right now, you’re hot. One day, you may be rich. One day, you may be famous. But this is the best,’” Lynch remembers. “He was right.”

But being too hot, of course, can burn, as Petty and the Heartbreakers were beginning to learn. A year later, their fourth album, Hard Promises, had not yielded the same payload of singles as Damn The Torpedoes, and the distractions were mounting: hard drugs, intra-band dramas, financial dilemmas, looming divorces, outside collaborations, stalkers, tonsilitis, interviews. As Petty told Circus in January 1983, “There are two things we can constantly do without even trying: spend money, and stay in trouble.”

Getty (3), Aaron Rapoport, Jim McCrary/Redferns/Getty

Two months earlier, the band released their fifth album, Long After Dark. Its 10 tracks represented the apotheosis of their work so far. Petty’s elliptical scenes of loneliness and alienation balanced atop a band with one foot in the past and the other in the future, with synthesizers and percussion pulling against Campbell’s incisive guitars, Lynch’s punchy drums, and Benmont Tench’s soulful piano. “It’s a good little rock’n’roll record with good songs and good playing,” Petty told Paul Zollo 20 years later. “But I don’t know that we advanced a lot.”