A HIGHER POWER

In 1972, the GRATEFUL DEAD embarked on their first bona fide European tour, a cavalcade of clown masks, switchblades and lashings of LSD. Fifty years on, as official releases loom for its legendar y soundboard treasures, the sur vivors celebrate some of the most extraordinar y music they ever made, and the last hur rah of the talismanic Pigpen. “It was pure Grateful Dead back then,” they tell GRAYSON HAVER CURRIN. “Magical and innocent and beautiful.”

The Dead park and ride on the Europe ’72 tour.

Gijsbert Hanekroot/Getty, Mary Anne Mayer

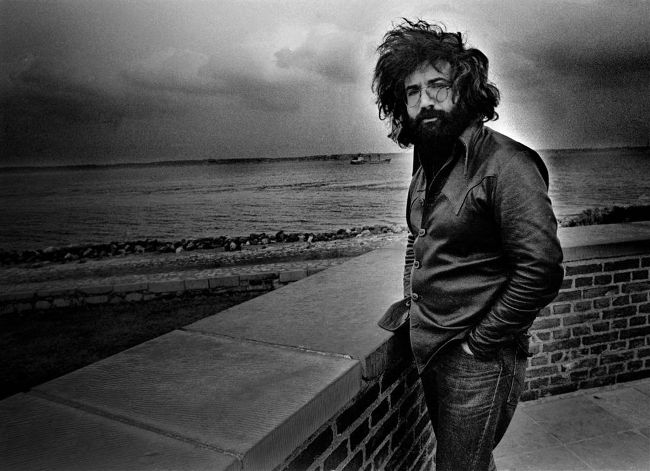

Pull the other one: Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia, Copenhagen, April 1972

Photographs: MARY ANNE MAYER, GIJSBERT HANEKROOT

Photofest, Getty, Mary Anne Mayer

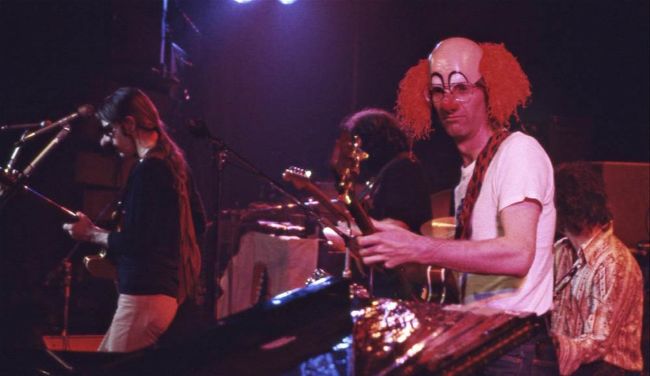

Foot down: the Dead in 1968 Mickey Hart, Phil Lesh, Garcia, Bill Kreutzmann, Ron ‘Pigpen’ McKernan, Bob Weir; a mountain view for the Dead, Europe 1972; Rolling Stones tour manager Sam Cutler at Altamont, December ’69, after which he joined the Dead; clowning around; Garcia twinkles.

THE POWER NEVER went out on the Grateful Dead the first time they toured Europe, in the Spring of 1972. Just months befor their transatlantic arrival, Dan Healy – the Dead’s steadfast audio technician and electrical handyman during their hazy San Francisco incubation – rejoined the crew after catching a Manhattan concert at the end of 1971 and being dismayed by its haphazard production. “It was dismal,” Healy tells MOJO. “The sound system was hopelessly inadequate. It wasn’t going in the right direction: light, bright, good.”

That night in New York, co-founder Jerry Garcia and drummer Bill Kreutzmann asked Healy for help. They were soon headed to Europe for a two-month tour of historic theatres that held thousands, and they needed their mountain of gear to work for these prospective fans. Healy began polling bands that had already toured Europe about the challenges – “Stage power,” members of The Rolling Stones’ entourage repeated.

“You could lose power on-stage by the fucking house lights going up,” explains Sam Cutler, who left his post as the Stones’ tour manager to handle the Dead soon after December ’69’s Altamont tragedy. “You’ve really got to know what you’re doing.”

Healy decided to eliminate the risk entirely, especially since so much of the Dead’s appeal depended on longform improvisation and at-will segues; losing power would devastate such flow. He invented a system that used massive wires to tap into a city’s electrical grid before it arrived in a centur y-old building like London’s Lyceum or Paris’s Olympia. The electricity then fanned out into a network of circuits the crew could control, independent of venues with outdated infrastr ucture. “If the whole theatre went down,” Healy says, “we would still be on.”

No other band had done something so daunting to ensure their performance remained uninterrupted, though the practice soon became de rigueur. Such willpower defined the Grateful Dead’s 22-show marathon through Europe, where a caravan of 53 California freaks thriving on a mix of acid, hash and booze not only found a new musical apotheosis but also reinvented perceptions of what a tour could be, how it could operate, and just what it could produce.

“We found ourselves on the cutting edge, not because our goal was to be on the cutting edge but because our goal was to see how good we could get it,” Healy says. “We had the willingness to seek out and develop.”

The Dead’s European debut proper represented a fortuitous confluence of preparation, circumstance, and what some on hand called magic. They had more than a half-dozen new songs to test on-stage with an inchoate line-up that included two keyboardists, only one drummer (after years with two), and a Southern soul singer. Two years after the release of Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty, they synthesized their roots impulses with the electrified wonder of their past and future. Inspired by scener y of ancient castles and verdant landscapes, they were simultaneously comforted and entertained by two busloads of family, friends, and employees they’d brought along for what guitarist Bobby Weir called a “working vacation”. They even had the foresight to record it all with emerging technology.

Indeed, less than six months after the tour ended, the Dead released a two-hour distillation of what they accomplished overseas, simply dubbed Europe ’72, that went double-platinum. Four decades later, the band released all 22 shows, bundling them together in an ostentatious edition housed inside a suitcase.

A half-centur y after that career-defining trip, the Grateful Dead are now revisiting 1972 for a spree of commemorative releases, including a remastered version of Europe ’72, a vinyl edition of the show at Wembley Empire Pool, and a set collecting the Dead’s commanding four-night finale at the Lyceum. They remain testaments to the Dead’s unprecedented moment of challenge and opportunity, vision and ambition.

“We had this notion that it may not seem doable, but we’re going to get it done because it has to be done. And if it has to be done, we’re going to do it,” says Weir, chuckling at his tautology. “That’s where we lived.”