MR INBETWEEN

WORDS JAMES McNAIR

FALLING BETWEEN STOOLSOF ROCK AND FOLK AND POP, THE

SONGS OF

ALAN HULL

–WRY,SEDUCTIVE, PALPABLY NORTHERN –

SHONE IN GEORDIE HITMAKERSLINDISFARNE AND ON CULT-STATUS

SOLO ALBUMS CHAMPIONED BY STING AND ALEX TURNER…

…SO WHY, ASKS MOJO OF HIS BANDMAT ES, DID HE MISS OUT ON

THE RECOGNITION HE DESERVED?

“HULLY WAS COMPLEX… DIFFICULT,

BUT HOW COULD YOU NOT LOVE SOMEBODY WHO WROTE SO BRILLIANTLY?”

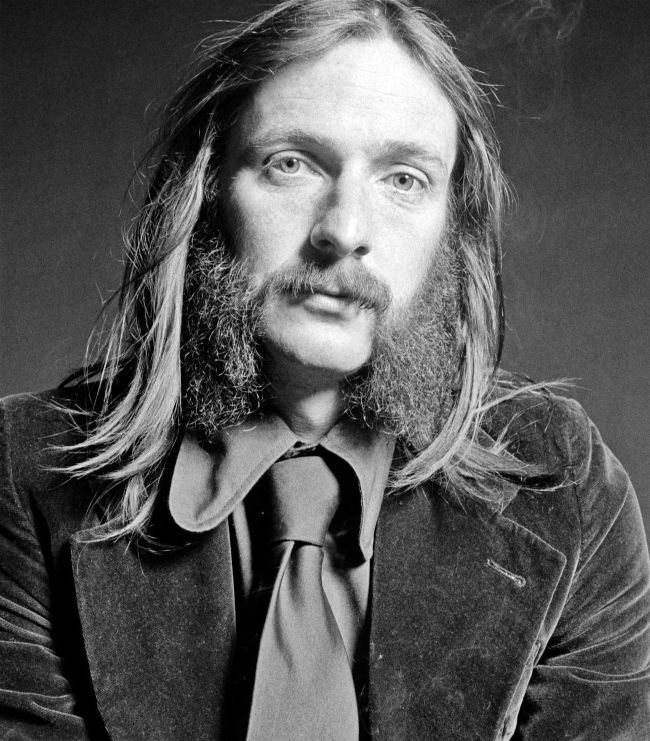

PORTRAIT

MICHAEL PUTLAND

The unlikely lad: Alan Hull, May 1974.

Getty/Michael Putland

IT’S 1967 IN GOSFORTH, NEWCASTLE AND ONE PSYCHIATRIC NURSE employed by St Nicholas Hospital has gone off-piste. Alan Hull is taking his patients down the pub, and it’s rumoured that he will only dispense mind-altering drugs he has already tried himself. Working nights, Hull reads Edgar Allan Poe, Blake and Herman Hesse’s Steppenwolf, literature to expand his consciousness with or without lysergics. If his patients need soothing, he plays them piano.

Part-inspired by Poe’s The Fall Of The House Of Usher, Hull has already penned Lady Eleanor, a mystical, mandolin-imbued augury of death which, in 1972, will become a huge hit for his as yet un-formed folk rock band, Lindisfarne. Like the searching, spiritually-charged Clear White Light and sparkling beacon for the homeless, Winter Song, Lady Eleanor evinces a poetic and pointed gift, and is one of some 300 tunes Hull will quickly amass during what Lindisfarne bassist Rod Clements today calls his “purple patch”. Nursing, Clements believes, took Hull deeper.

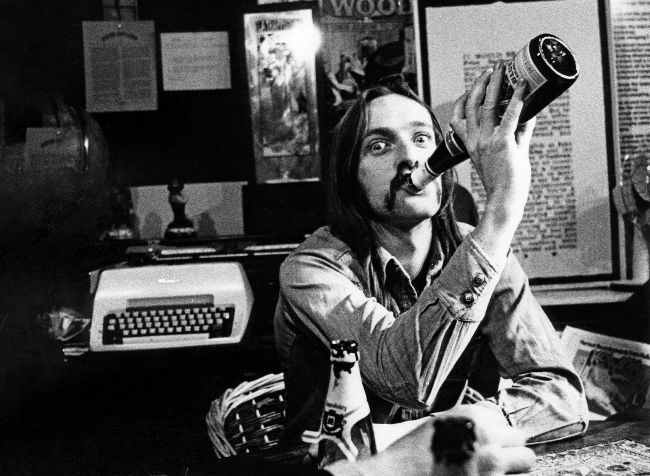

One more bottle of wine: Alan Hull toasts his good fortune in Warner Bros’ London offices, 1974.

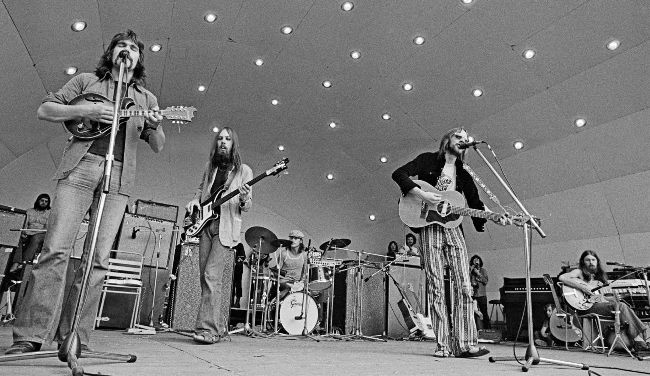

Getty (3)

Happy daze: Lindisfarne on-stage at the Crystal Palace Garden Party, September 2, 1972 (from left) Ray ‘Jacka’ Jackson, Rod Clements, Ray Laidlaw, Alan Hull, Simon Cowe;

“Alan came away from St Nick’s with his eyes opened to the workings of the mind and more universes than most of us get to see,” Clements tells MOJO today. “He didn’t regard his patients as having something wrong with them; he just thought they had a different outlook.”

For Sting, who grew up near Impulse Studios in Wallsend, where Hull demoed early material, Lindisfarne’s chief songwriter was “our Bob Dylan”, a potent local voice with a seer’s articulacy. But Lindisfarne drummer Ray Laidlaw holds that, for all his talent, Hull was also “a lazy fucker who could never have been a Ray Davies or Frank Zappa type, because he wanted it all on a plate.”

“Humanist, songwriter and poet”, reads the blue plaque dedicated to Hull outside Newcastle City Hall. Local hero? Certainly. But what made this bibulous, vehemently antiestablishment figure tick, and why are some of his greatest songs still relatively unknown?

HULL’S STINT AT ST NICK’S EARNED HIM a wage after his sharp exit from The Chosen Few. Big on Beatles-esque originals and Motown covers when Hull joined on guitar and vocals in 1965, the Few had signed to Pye and played Hamburg. But in an early instance of Hull’s wilfulness, he was fired from the band for refusing to bowdlerise his left-wing protest song, This Land Is Called, as demanded by Pye’s head of A&R Cyril Stapleton.

Future Lindisfarne players Clements, Laidlaw, Ray ‘Jacka’ Jackson and Simon Cowe had already clocked The Chosen Few around Newcastle and been impressed. “It was his whole demeanour,” says Clements of Hull. “He had a confidence and a sort of arrogance that was very fashionable at that time.”

Meanwhile Clements, Laidlaw and Cowe’s Chicago blues band The Downtown Faction grappled with a downturn in the Brit-blues boom, and, struggling to retain singers, had one eye on Hull. After leaving St Nick’s, Hull was running a folk club at The Rex Hotel in Whitley Bay, playing solo sets alongside visitors including Ralph McTell and Al Stewart, and it was there, having won a copy of Bert Jansch’s Birthday Blues in the raffle, that Clements finally spoke to him.