GOLDEN BELLS

In early 1973, a 19-year-old musician from south-east England was on the cusp of mega-stardom as he prepared to release his debut solo album. Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells was unlike anything else at the time and went on to transform the former folk artist into a multi-platinum-selling global sensation. In an exclusive interview for Prog, Oldfield celebrates the groundbreaking ambient record’s 50th anniversary reissue with the story of its creation and the sequels it inspired.

Bell ringer: Chris Wheatley

Portrait: Michael Putland/Getty Images

Undoubtedly one of the most naturally gifted musicians ever to have come out of England, Mike Oldfield celebrates his 70th birthday this year, which coincides with the 50th anniversary of his first solo album, Tubular Bells. Born in Reading, Berkshire, Mike’s first professional music experience came as half of folk duo, The Sallyangie, alongside his sister Sally. He then came to the attention of Kevin Ayers, playing on two classic albums, Shooting At The Moon and Whatevershebringswesing. By 1971, Oldfield was a bassist in blues-rock group The Arthur Louis Band and worked on solo material in his spare time. It was in September of that year that a fateful meeting occurred. The Arthur Louis Band decamped for recording sessions to The Manor Studio in Oxfordshire, a newly built facility owned by businessman Richard Branson and run by producer-engineers Tom Newman and Simon Heyworth.

“Tubular Bells I is still my favourite, because it remains unique and has stood the test of time. I can’t believe it’s 50 years since it was released.”

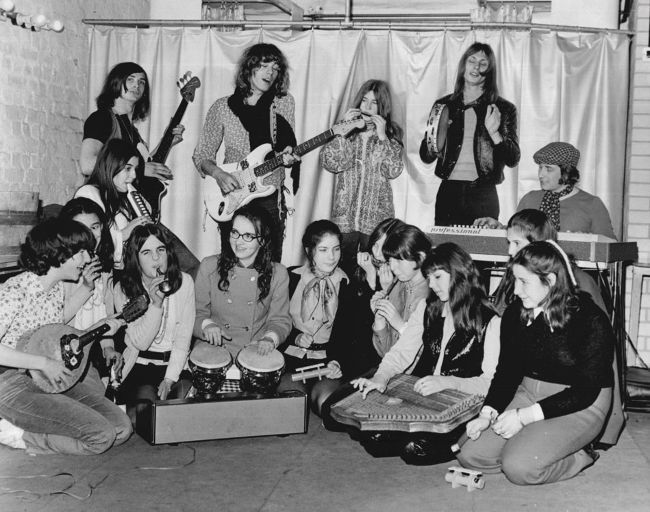

The choir of a girls’ school appeared at the Roundhouse Theatre in London with Kevin Ayers And The Whole World in 1970. Mike Oldfield is on the left.

JAMES GRAY/ANL/SHUTTERSTOCK

“I had no idea at all how the album would be received. My demo had been turned down by so many record companies during the previous year.”

It was Newman and Heyworth who first heard the solo material that Oldfield was working on. Impressed by the young multi-instrumentalist’s skill and vision, the pair were determined to record his work. They soon talked Branson into allocating official studio time for Oldfield’s project and the finished album went on to become the very first release on Virgin Records. Since then, Tubular Bells has grown into a phenomenon, and Mike Oldfield has enjoyed a long and illustrious career. Speaking from his home in the Bahamas, Oldfield talks with passion of his formative musical experiences. “I remember awakening to the existence of music when I was about six years old,” he says. “Our family had a Dansette record player at the time and my earliest memorable tune was The Teddy Bears’ Picnic. I tried to request it on the radio but they never played it for me.

“Then I began to hear my mother playing Puccini’s opera, Madama Butterfly, which was probably the first classical music I ever heard. Then my sister started playing a lot of Elvis Presley and Mario Lanza arias, until one day I came home from school and heard an amazing track playing on the Dansette. I found out it was Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. It really had a profound effect on me, even as a child of six – my jaw dropped, and I thought: what is that? I was enraptured by it.”

The uniqueness of Oldfield’s childhood isn’t lost on him.

“I was lucky to be born in an amazing era for music – the dawn of the 60s and the birth of rock’n’roll. The Beatles and the Stones were releasing their first records and more and more exciting music was being born all the time. So I was riding the crest of that wave as a young listener for over 10 years, at the same time as I was developing my own musical skills.”

Mike Oldfield at The Manor Studio in Oxfordshire, where both Tubular Bells and its follow-up, Hergest Ridge, were recorded.

BARRY PLUMMER

Tubular Bells And Me: Simon Heyworth (The Producer)

Engineer and producer Simon Heyworth has worked with a host of prog greats over the years, but back in the early 70s he was learning his trade on the job, alongside Tom Newman, creating The Manor Studio from scratch in a Grade II-listed building.

What are your memories of putting together The Manor Studio?

It took us about a year and a half. I learned all about recording consoles and microphones and all the rest of it. It was mainly Tom and I to start with. During that whole first couple of years, there’s me learning everything about mixing and, of course, [chief engineer] Phil Newell was a true tremendous influence; he had a great knowledge. I was a tape operator to begin with, then I started sitting in and mixing and recording and so on.

When did you first encounter Mike Oldfield?

One morning, we were playing around with recording and Richard [Branson] sent down this group called The Arthur Lewis Band. In this band was a young guitarist called Mike Oldfield. We were still trying to get the studio together. The place was littered with equipment. We had this huge, transistorised console set up in the house and downstairs there was sort of a tiny, cosy room, with quite a lovely view out into the garden. In the mornings it would be very sunny. I came down about five o’clock one morning to find Mike sitting on the floor in this lovely room, the sun was coming up and he was playing the opening riffs of Tubular Bells. Mike was over-dubbing on our quarter-inch two-track machine. He’d discovered that if you covered over one of the components and reversed the wires, you could record four tracks going in one direction. Beautiful. To this day, I will never, ever forget that, because it’s the beginning of it right there. I said to him, “We’ve got to record this.”

What was the recording process like?

Eventually, we were given an official week and we started recording. We thought, “How the hell are we going to do this?” I had this idea [and] we set up a metronome in another room so we could get some semblance of timing for the first piece, because it’s 20 minutes long. We also thought, “How the hell are we going to overdub this? It’s going to be difficult working out what bits start where and all the rest of it.” We got this enormous 16- track Ampex from America. Mike didn’t like playing to a metronome, so that was quite difficult. But anyway, by the end of the first week we had some semblance of the beginning. From then on, it happened in dribs and drabs, recording whenever we could and whenever Mike was available.

I remember, near the end, I recorded this piece of guitar, it might have been the final acoustic piece we recorded. I recorded this beautiful playing in the late at night. And you know it was stunning, I mean Mike just played so beautifully. It brings tears to my eyes sometimes to think about it. He has a real gift with his acoustic work. And I always say, it would be so nice if he just picked up an acoustic guitar and did an acoustic album. Absolutely lovely.

Were you surprised by the album’s success?

By the time it was a hit it had kind of already been a hit in my head for many years. I mean, I walked around with that in mind. So when we finally got a gold record and it was a big seller, it didn’t surprise me, funnily enough. I mean, it really didn’t.

The original plan wasn’t for Richard Branson to release the record himself…

No, not at all. I remember Tom [Newman] and I going to Richard and saying, “Why don’t you release it yourself?” And then, of course, once he’d decided it was going to happen, Richard did what Richard always did, which was have some fun with it. He booked the Queen Elizabeth Hall to do a live show, but we knew that Mike certainly would not want to do that. So we thought, “We’ll do some rehearsals, we’ll get the band, then we’ll just tell Mike that it’s happening. And then he might actually agree,” because he didn’t have to organise anything. I had the idea to go to Shepperton Studios, because my brother was in the film industry. My brother knew that they had a soundstage they didn’t use and it was big – a hanger, basically – and they had all this wonderful old recording equipment, which was absolutely fascinating for me. We got this soundstage for something like 300 quid a day.

Why do you think Tubular Bells has stood the test of time?

It’s a lovely piece of music, as simple as that. It’s just really interesting, lovely and unique. In those days, people actually listened to entire records religiously: you’d put it on the turntable, sit on your cushions and listen, and music was a very special thing. You have to think about it in those terms and I think it just is simply such a lovely piece of music, with beautiful playing and, there’s no doubt about it, it’s very moving.