Contain yourself

Containerisation is even more of an ugly word than virtualisation, but it’s a big deal too. A Docker whale-sized big deal, as we’ll discover…

A

decade or so after the rise of VMs came the rise of containers, and in particular Docker. Containers are the spiritual successors of BSD jails and chroots, but rely on modern features in the kernel, namely cgroups and namespaces, which means applications can be apportioned resources and run in isolation.

Chromium

uses this for sandboxing and so do the new Flatpak and Snap packaging formats.

Containers use the host’s kernel, and whatever resources you allow them, and in so doing enable applications and their dependencies to be packaged up and run anywhere. You could call it application rather than machine virtualisation, but whatever it is it does away with the need for a whole OS to be packaged up, so things are, in theory, lighter, faster and easier. Containers don’t enjoy quite the same physical separation (from each other and the host) as virtual machines, but Spectre and Meltdown have highlighted VM security in this regard and Docker exploits are probably quite hard to pull off.

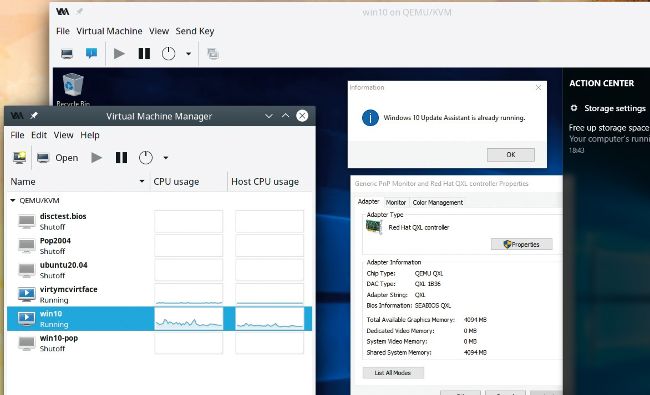

Here’s virtual Windows 10 in action, complaining about disk space and with a confused Windows Update. Just like the real thing, to be brutally honest.

In our Chess feature (page 40) we saw how easy it was for Nvidia users to get a CUDA-enabled Leela Chess Zero Docker image up and running. Docker has a bit of an advantage over VMs for situations like this that require direct access to hardware. Containers can be granted the privilege to access these things unimpeded. But lots of effort has gone into making virtual GPUs as fast as they can possibly be, and you should check the box to familiarise yourself with some of them.