Paleo Diets and Utopian Dreams

BY ADRIENNE ROSE JOHNSON

“LIFE WAS GOOD FOR OUR PALEOLITHIC GRANDparents,” recounts a 2001 diet book.1 A 2013 diet laments that civilization has “transformed healthy and vital people free of chronic diseases into sick, fat, and unhappy people.”2 If everyone went Paleo, one dieter interviewed for this article explained, “the world would be a more beautiful, healthier place, and we all would be more healthy, better people.”3

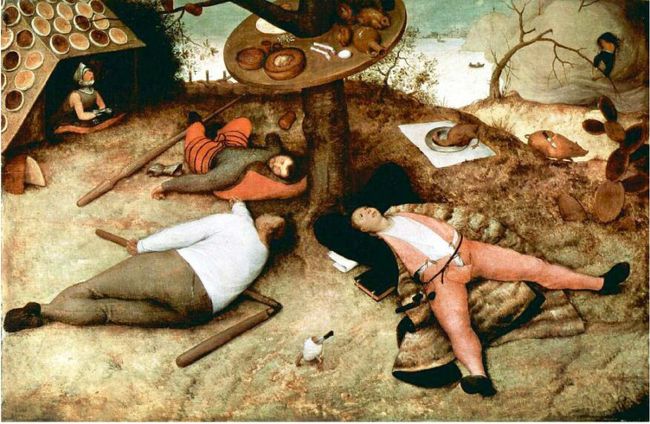

Figure 1—The Land of Cockaigne (1567) by Flemish artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

An estimated three million Americans currently follow some version of the Paleo diet, and Paleo books are among the bestselling titles within an already blockbuster genre.4 At its most basic, Paleo diets reject agricultural products such as cereals and sugars for foods that could have been hunted or gathered—mostly high-fat, high-fiber meats and plants. In practice, “going Paleo” means everything from the ordinary to the outlandish.5 On the latter end of the spectrum, some dieters avoid artificial light, eat raw beef, forsake shoes, practice bloodletting, engage in polyamorous sexual relationships, and “adopt a primal attitude,” whatever that means.6 For others, the diet is just that: a diet of mainly meat and vegetables (occasionally fruits and legumes) adopted to lose weight or gain muscle. Most dieters practice Paleo to lose weight, but this “species-appropriate diet” allegedly cures more than a hundred ailments, ranging from Alzheimer’s to anxiety, epilepsy to acne.7

Despite its popularity, the Paleolithic diet has received little scholarly attention. The diet is not merely a collection of weight loss manuals but a complex and controversial social movement indebted to a long history of primitivist nutritional counsel, divided by bitter philosophical splits, alternately mocked and praised by mainstream medicine. The whole weight loss narrative genre has much to offer an interdisciplinary study of utopia and, in particular, the caveman diet offers an embodied utopian practice embedded within a powerful story of an original, lost Paleolithic paradise.

But the caveman diet is more than a myth of a lost golden age and more than a handbook for weight loss: the diets are at once a manual for the body, the self, and society. Paleo diets have been heralded as the best “way of life,” a “revolution,” and, most important, the “first glimpse of a new and better world.”8 The Paleo diet differs from most self-help literature by linking corporeal and social transformation, enlisting the body to measure and materialize the processes of recouping the utopia within. These diets uphold social dreams with shared origins (in the cave), a collective problem (the obesity epidemic), and common ends (health for all). As the 2013 Paleo Manifesto puts it, the diet aspires “to understand where we come from, to make the best of where we are, and to craft a better future.”9

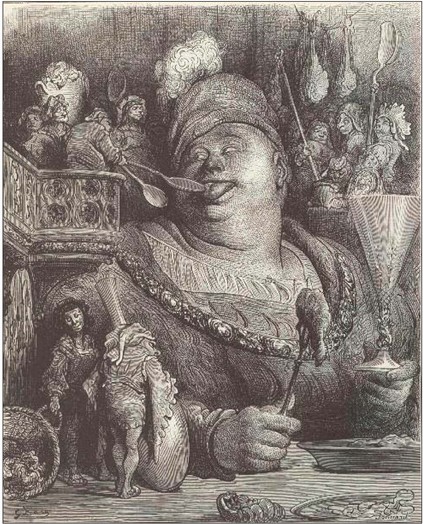

The caveman diet mixes myth and manual to create a new and different type of embodied utopia. Traditionally, body utopias are modeled after the old, medieval model of binging and reckless overindulgence. Imagine paintings like Bruegel’s 16th century The Land of Cockaigne (left): peasants, passed out on cobbled streets, stuffed to the gills with meat pies and puddings and sausage. Or the carnival fantasy of the 16th century novels The Life of Gargantua and of Pantagruel (right) and their visions of grotesque, celebratory excess. But the Paleo diet today represents a radical departure from this older model—slow, moderate, nuanced, delicate experiences of appetite and natural flavor.

The story is told like this: Since agriculture is such a recent invention on the timeline of human evolution, “our genes are still in the Stone Age,” and we must follow “what our ancient ancestors ate” to recapture “our natural birthright of health.”10 We are “literally Stone Agers living in the Space Age” and time has sped too fast for our bodies to adapt.11 Ill-adapted and clumsy in this strange new world, our modern bodies have become sick, fat, and stressed. In this narrative, the Paleo diet situates the individual body in the long, deep currents of human history, suggesting that the body is on loan from history and obliged to the future—and only one’s own property for a short-lived half-blink of evolutionary time.

The Caveman Diet Subgenre, or, “Bread Is the Staff of Death”

Western weight loss literature has a long tradition of venerating “primitive” diets and ways of life. Since the 19th century, influential American diet reformers conjectured about the diets of preagricultural peoples and recommended these “natural” foods to cure ailing moderns. In the 1890s, Dr. Emmet Densmore popularized a meat-heavy diet inspired by the “food of primal man,” claiming that “bread is the staff of death” and “imbecility, decrepitude, and premature death go hand in hand with luxury and plenty.”12 “Primitive” diets were not restricted to Densmore’s “anticerealism” or the low-carb cause.13 Throughout his long life, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg (1852-1943) also speculated on “the ways and likings of our primitive ancestors of prehistoric times” to support his diet of grains and other farinaceous (starchy) foods.14

Known by many different names—the caveman, Stone Age, evolutionary, primal, or hunter-gatherer diet—Paleolithic diets have also long been bound into larger political and social visions. In his time, Kellogg’s anti-masturbation crusades and suspected pantheistic sunflower worship won him greater fame than his cereals. In 1975, Dr. Walter Voegtlin was the first to publish a full-length diet book explicitly modeled after theories of Paleolithic nutrition—his self-published The Stone Age Diet— but Paleo leaders today have largely disavowed Voegtlin for his white supremacist, eugenicist, and generally unpalatable politics. Bizarrely, Voegtlin recommended the mass slaughter of tigers, dolphins, and other carnivores.15 “Will [dolphins] be eliminated, or will man?” Voegtlin asked his readers, gesturing toward an apocalypse in which dolphins, fat on fish, overrun the world with their well-fed populations.16

Figure 2—Gargantua from François Rabelais’ satircal novels.

Disagreeable or eccentric views like these dominated discussions of the “caveman diet” until the January 1985 New England Journal of Medicine article on Paleolithic nutrition advancing the “evolutionary discordance hypothesis” by S. Boyd Eaton and Melvin Konner, both distinguished medical doctors with anthropological training.17 The discordance or “mismatch” hypothesis theorizes that the clash between “ancient body and modern world” produces obesity, diabetes, and the other “diseases of civilization” or, as they are sometimes called, diseases of affluence, longevity, environment, or lifestyle.18 Eaton and Konner argued that since “the human genetic constitution has changed relatively little since the appearance of truly modern human beings, Homo sapiens sapiens,” pre-agricultural diets provide the “nutrition for which human beings are in essence genetically programmed.”19