Framed?

How Sensationalism Keeps New York City’s Most Controversial Defendants Innocent in the Eyes of the Public

BY JOHN D. VAN DYKE

New York, New York, the “city that never Sleeps,” has given us two Presidents, Eggs Benedict, potato chips, Robert De Niro, Saturday Night Live, and Scrabble. Two of New York City’s boroughs have also been home to three of the most controversial and infamous criminal defendants in American history: Bruno Richard Hauptmann, and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

Though their convictions were handed down decades ago, Hauptmann from the Bronx, and the Rosenbergs from Knickerbocker Village in Manhattan, remain causes célèbres around the globe. With passionate proponents around the world still proclaiming their innocence, a skeptical examination of the evidence for the guilt of both Hauptmann and the Rosenbergs is warranted.

Bruno Richard Hauptmann

The Crime

On the night of March 1, 1932, 20-month-old Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. was kidnapped from his nursery window on the second floor of the Lindbergh home near Hopewell, NJ.1 The kidnapper(s) left a poorly written ransom note demanding $50,000 (over $1 Million in today’s money).2 The note to the Lindbergh’s also contained a code: two interlocking circles resembling a Venn diagram with three small holes punched through them.3 At least two sets of differing footprints were found at the crime site, as were a ¾” chisel,4 and the home-built ladder used to climb to the nursery window.5 During the next three months, 13 more notes bearing the code symbols were delivered and the ransom was raised to $70,000.

The kidnapping of the world-famous son of “Lucky Lindy” (solo pilot of the first nonstop airline flight across the Atlantic Ocean, New York to Paris) made international headlines. A retired school teacher and, by all accounts, a self-aggrandizing publicity-seeker6 named John F. Condon, published a letter in the Bronx Home News offering to serve as a liaison between the Lindberghs and the kidnapper(s).7 On March 8, seven days after the child was taken, and one day following the publication of his offer, Condon received a letter, bearing the code, accepting his offer to be an intermediary.8

Condon was instructed by the kidnapper(s) to place an ad in the New York American using the name “Jafsie” (a play on his initials), indicating that the ransom money was ready. Condon did so and, on March 12, he received another code-bearing letter from a cab driver instructing him to meet the kidnappers at Woodlawn, a Bronx cemetery.9 Condon went alone. There he met a man with a German accent identified as “John,” who asked for the money, which Condon refused to provide until he’d seen the baby. The mysterious man expressed fear that he “might burn” if the baby was dead and told Condon he would provide proof of the child in the toddler’s sleeping suit.10 Condon soon received the child’s sleeping suit in the mail and continued to communicate through advertisements until a meeting was arranged to exchange the ransom. $70,000 in unmarked gold certificate U.S. paper money were placed in two packages, their serial numbers having been recorded. (The fact that the ransom was paid in gold certificates would later become significant).

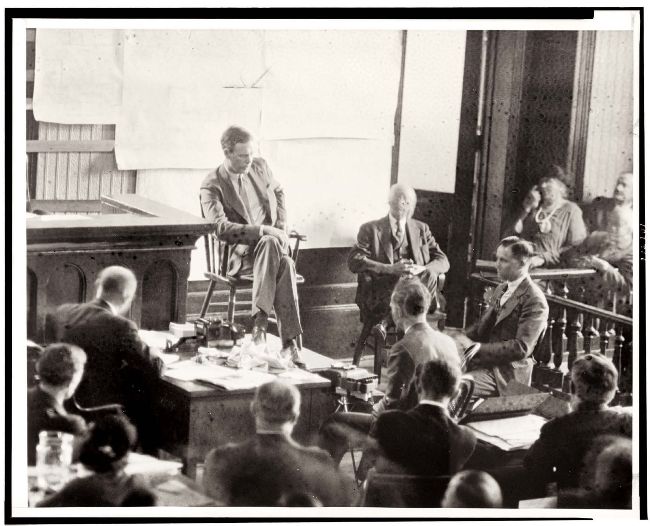

Charles Lindbergh testifying at the murder trial of Bruno Hauptmann, January 1935.

On April 2, 1932, Charles Lindbergh rode with Condon11 to another Bronx cemetery, St. Raymond’s,12 where they heard a man call out, “Hey doctor!” Condon went toward the voice while Lindbergh waited in the car. Condon convinced the kidnapper he only had $50,000 of the ransom money. The kidnapper accepted the sum and gave Condon another note filled with misspellings asserting that the child was safe aboard a boat named “Nelly,” harbored off the Massachusetts coast.13 The kidnapper took the money and Condon returned to the car where Lindbergh was waiting. An exhaustive search failed to find the boat. On May 12, 1932, the body of the child was found close to Lindbergh’s home from which he was taken.14 Over the next two years, 296 of the gold certificates the Lindberghs used to pay the ransom turned up in circulation.