LXF SHELL

The LXF Shell in… the redirection redemption

Ferenc Deák continues writing shell-enhancing redirection features and hiding the odd film title for you to spot, the little scamp!

OUR EXPERT

Ferenc Deák is sure that the usual suspects of programming languages fit for writing a shell have been exhausted, so he sticks to C++.

QUICK TIP

The code for the LXF Shell can still be found at https://github. com/fritzone/lxf-shell.

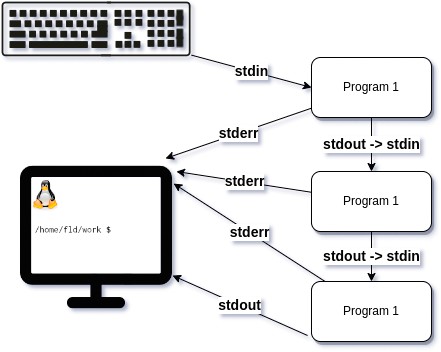

Previously in our LXF Shell series, we reached a stage P where we could execute applications (LXF310), and looked at how to properly redirect the output of an application (LXF310). For this latest instalment, we are planning how to implement the input redirection for the shell, and as a final touch, how to bring all these together and create a shell that can sequentially execute applications by piping input and output between them.

Input redirection

Linux input redirection in a shell enables you to change the source of input for a command or program. It is accomplished with the < operator, by adding < to redirect the standard input (stdin) of a command or program from a file instead of the keyboard after the command, and specifying a filename whose content is read and used as input for the command to be executed. For example: wc -l < input.txt .

In this example, wc -l reads its input from the input. txt file instead of waiting for keyboard input, and counts the lines in that file. Input redirection can be particularly useful when working with scripts and batch processing, because it enables you to automate tasks and process large volumes of data without manual input.

From a programming point of view, input redirection happens in a similar way to output redirection, using pipes, as the following program exemplifies. To save precious space, we have omitted the error checking; however, the example code found at https://github. com/fritzone/lxf-shell has all the necessary checks and comments, so be sure to check it out. int main() { int pipe_fd[2] = {-1, -1};

This diagram represents how pipe interactions can happen in Linux.

Part Three! Don’t miss next issue, subscribe on page 16! pipe(pipe_fd); pid_t child_pid = fork(); if (child_pid == 0) { close(pipe_fd[1]); dup2(pipe_fd[0], STDIN_FILENO); close(pipe_fd[0]); char program_name[] = “wc”, *args[] = {program_ name, NULL}; execvp(program_name, args);

} else { close(pipe_fd[0]);

FILE *input_file = fopen(“input.txt”, “r”); char buffer[4096] = {0}; size_t bytesRead = 0; while ((bytesRead = fread(buffer, 1, sizeof(buffer), input_file)) > 0) write(pipe_fd[1], buffer, bytesRead); close(pipe_fd[1]); wait(NULL);