1970s

Riding In The Sky

OF ALL THE BEATLES, PAUL MCCARTNEY WAS REGARDED AS THE ONE WITH THE COMMERCIAL POTENTIAL. HE WAS, THEREFORE, ALSO ARGUABLY THE ONE UNDER MOST PRESSURE TO SUCCEED IN THE SEVENTIES. BUT DID HE? WELL, HE DID AND HE DIDN’T…

PAUL LESTER

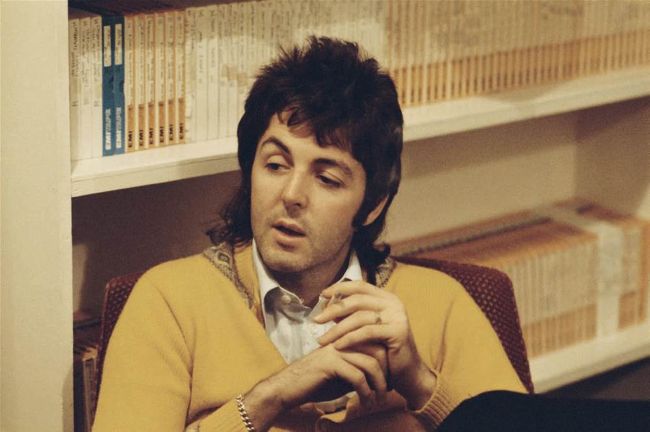

A generously mulleted Paul, 21 November 1973

© Getty Images

The First year of the Seventies saw all four ex-Beatles keeping busy. George Harrison found himself at No. 1 across the universe with his triple album All Things Must Pass (not bad for “the quiet one”), Ringo Starr found himself at No. 7 and No. 22 in the UK and US with his solo debut Sentimental Journey (not bad for an album without a single to promote it) and John Lennon recording, with Starr on drums, the excoriating avant-garde confessional John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band, which reached the Top 10 of most of the world’s charts (not bad for an excoriating avant-garde confessional).

1970’S SELF-PERFORMED MCCARTNEY ALBUM ESCHEWED SOPHISTICATION FOR A MORE HOMESPUN FEEL, WITH A RAGGED AND RAW LO-FI CHARM

As for Paul McCartney, he wasted no time in putting his stamp on the new decade. In fact, he began working on his first solo release in the last month of the previous decade, on a Studer four-track tape machine. It comprised material he’d variously written in India, during the Let It Be sessions, on his High Park farm in Campbeltown, Scotland and at home on Cavendish Avenue in St John’s Wood in London. Recording and mixing took place at Morgan Studios and Abbey Road, but if the latter legendary studio led long-term Beatles-watchers to expect a feast of overdubs and multilayered symphonic delights, they would have been disappointed with the finished product.

McCartney, issued in April 1970 –a month before the “posthumous” 12th and final Beatles album, Let It Be – eschewed musical sophistication for a more homespun feel, with a ragged and raw lo-fi charm that anticipated the alternative/indie ethos of the Nineties and beyond, with McCartney the prototype for legions of bearded DIY hipsters.

A mixture of worked-up demos, doodles and fully-formed songs, the album was an entirely selfperformed affair, McCartney handling all vocal and instrumental duties (acoustic and electric guitars, bass, drums, piano, organ, percussion, Mellotron, toy xylophone, even a bow and arrow and wine glasses), with assistance only from his new wife, Linda, on harmony and backing vocals. It appeared to usher in a new era of self-sufficiency (or solipsist studiomania, depending on your view), with Stevie Wonder and Todd Rundgren (and, later, Prince) soon venturing forth as do-it-all singer-player-producers (indeed, cult California artist Emitt Rhodes, virtually simultaneously, was singing, playing and producing every note of his own selftitled album in 1970).

For McCartney, this was therapy. And the results were like listening to a man picking up the pieces of his life from the wreckage of a tumultuous crash. Staggered, dazed and metaphorically bleeding from the death throes of The Beatles, McCartney saw the musician seeking solace in pure sound. “It was a release, a freedom thing for me, an escape,” he reflected in 2010. “I wanted to get back to basics.” On McCartney he rediscovered the rough-hewn atmosphere he had originally envisaged for Let It Be, before Phil Spector added his magniloquent flourishes. “I like its bare bones,” McCartney said of his debut solo foray, which in its own eccentric way was every bit as personal and cathartic an exercise as his erstwhile partner’s John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band. “Talk about honest. You couldn’t get more honest.”

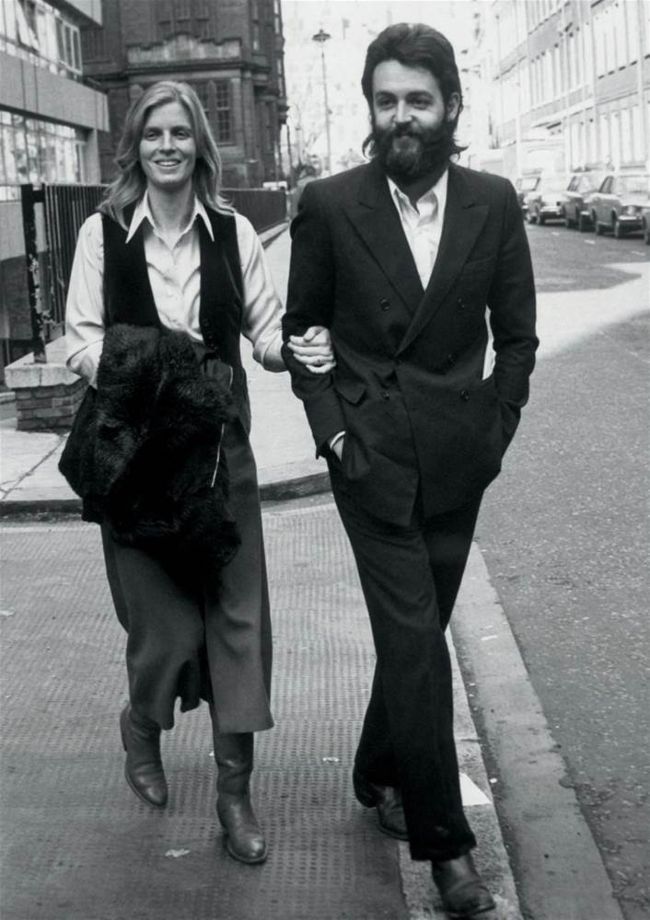

1971, and Paul and Linda emerge from London’s Law Courts after a hearing on the dissolution of The Beatles

© Getty Images

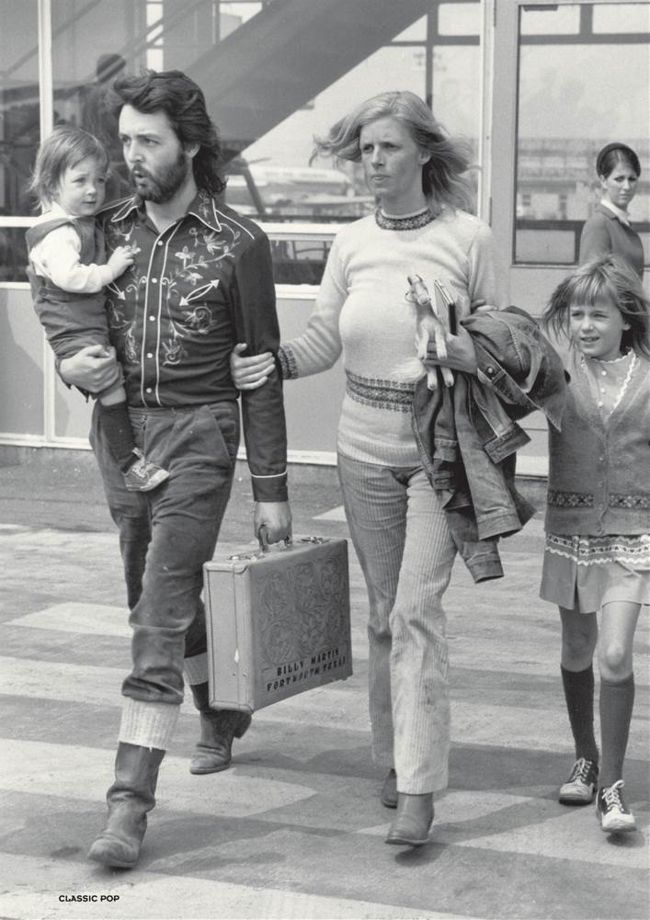

Paul holds daughter Mary at Gatwick Airport as the family travel to Copenhagen, May 1971

© Getty Images

The album opened with The Lovely Linda, his shortest ever composition, 42 seconds of gentle whimsy that set the lo-fi, noodley tone. The simple, down-home acoustica of That Would Be Something furthered the sense of a rock musician getting his proverbial head together in the country, Macca’s Scouse brogue slipping easily into bluesy vocalese. Valentine Day, a sketchy instrumental, was followed by the deceptively tuneful Every Night, a paean to the missus that credited Linda with saving him from the fallout of The Beatles’ final days, with their concomitant tendency towards self-destructiveness and depression. “Every night I just wanna go out/And get out of my head,” he sang. “Every day I don’t wanna get up/ Get out of my bed… But tonight I just want to stay in and be with you.”

Hot As Sun/Glasses was an instrumental medley, the second half of which featured wine glasses being played at random then overdubbed, as well as a brief music hall coda. Junk, penned in 1968 when The Beatles were in India at the Maharishi’s holiday camp, was a nice, pretty strumalong with melodic intimations of Mull Of Kintyre and, in the chorus, of Mamunia from 1973’s Band On The Run.

Man We Was Lonely essayed a new paradigm: jaunty despair. Finding Paul channelling his inner Johnny Cash, it was the first song that Paul and Linda wrote and sang together as a duet (making it, in a way, a precursor to Wings), and one of the last that they recorded for the album. It explored their feelings for each other, having respectively divorced Melville See Jr and broken up with actress Jane Asher. Oo You showed that McCartney could do Yer Blues-ish rasp’n’roll, Kreen-Akrore was based on a TV film about the Kreen-Akrore Indians in the Brazilian jungle, Momma Miss America pivoted on moody bass and keyboard chords, and Teddy Boy was another track originally written with The Beatles during the Let It Be sessions. The latter seemed more fully-realised than most of the other semi-songs on the album, with the famous notable exception of Maybe I’m Amazed, which even critics of the album (who included George Harrison) had to admit was an excellent late addition to the McCartney canon. Written in 1969, as The Beatles were careening to a halt, and an expression of gratitude to Linda for helping him through it all, McCartney described it in 2009 as “the song he would like to be remembered for in the future”, although it wasn’t issued as a single (until a live version came out in 1977).