THE WEIRD WORLD OF AIRSHIPS

Pioneering aircraft that captured the imagination of a generation, airships have a brief but action-packed history

WORDS PETER WOLFGANG PRICE

The accepted future of air travel today is firmly in the hands of planes, but at the end of the 19th century it was airships that held the keys to the sky. Floating leisurely above the clouds, the story of these craft has often been forgotten and sidelined in favour of fixed-wing aviation achievements, but remains a key part of humanity’s history of flight.

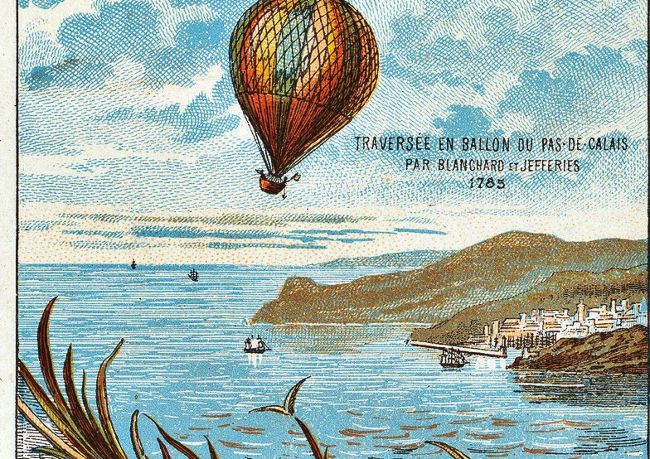

Blanchard’s successful crossing of the Channel made him a celebrity

BALLOONMANIA STRIKES EUROPE

1784

Jean Pierre Blanchard was a Frenchman who dreamed of flight. The owner of an inquisitive mind, he unsuccessfully attempted to develop manual-powered aeroplanes and helicopters before finding fame with another aviation idea: hot-air balloons. In March 1784, Blanchard first took to the skies in a homemade balloon, a year after the first successful balloon flight by the Montgolfier brothers. In 1785 he teamed up with an American physician, Dr John Jeffries, and lifting off from Dover Castle flew over the English Channel to France. The journey took a leisurely two-and-a-half hours and was a world first. Blanchard’s flights triggered ‘balloonmania’ among the public, with all manner of balloon memorabilia being produced. However, Blanchard would suffer an unfortunate end when he had a heart attack mid-air in 1808. Plummeting 15 metres to the ground caused massive injury that he would never recover from, and he died the next year.

DID YOU KNOW? Future airship spacecraft might be used to explore the clouds above Venus and Jupiter

A CHANGE IN DIRECTION

1852

Just 51 years before the Wright brothers conquered the skies, the first powered flight in history was taking place. French engineer Henri Giffard had solved a major problem with balloon travel: controlled and steerable propulsion. Without this, a balloon ride was essentially a one-way trip. Creating the world’s first powered and steerable airship, called a ‘dirigible’ from the French word for steerable, Giffard had opened the world up to the concept of lighter-than-air travel. The gas used in balloons at this time was hydrogen, which was highly flammable and dangerous, but was otherwise lighter than air, allowing for balloons filled with it to float. To power his dirigible, Giffard used a steam engine specially designed with a downwards-facing funnel and mixed exhaust fumes so as to reduce the chance of sparking – just one of which could vaporise the volatile hydrogen. Producing three horsepower and able to reach a top speed of more than nine kilometres per hour, the engine was about as powerful as a modern iron.