FORTRAN

FORTRAN – the first high-level language

It might have been the world’s first high-level language, but Mike Bedford discovers that FORTRAN is still alive and well today.

Credit: https://fortran-lang.org

OUR EXPERT

Mike Bedford discovered that even though it’s very different from modern languages, it’s easy to get up to speed with the original FORTRAN as it has just 32 instructions.

QUICK TIP

If you catch the FORTRAN bug, you might be interested to learn about the open source LFortran project. Put simply, it’s an interactive version of FORTRAN that enables you to try out ideas, getting immediate results, without having to compile any code. In this respect, it’s been likened to Python, MATLAB and Julia.

When FORTRAN was first conceived, there were barely any high-level languages, and certainly none that became widely known. With such languages now virtually universal, we need to remember that high-level languages were designed to ease the job of a programmer. Previously, code was written in a computer’s native instructions, which were defined by the computer’s hardware. Using a high-level language, it became possible to use instructions that were closer to how humans would define the solution to a problem. Productivity gains, it was argued, would follow. Programs could also be transportable between different computers, although this wasn’t a consideration when designing FORTRAN, because the language was initially designed specifically for the IBM 704 computer.

The original FORTRAN was introduced in 1957 and had just 32 instructions, a far cry from most of today’s languages. What’s more, several of these instructions were tied up to the IBM 704’s hardware, so they were removed from later versions that were intended to be hardware independent.

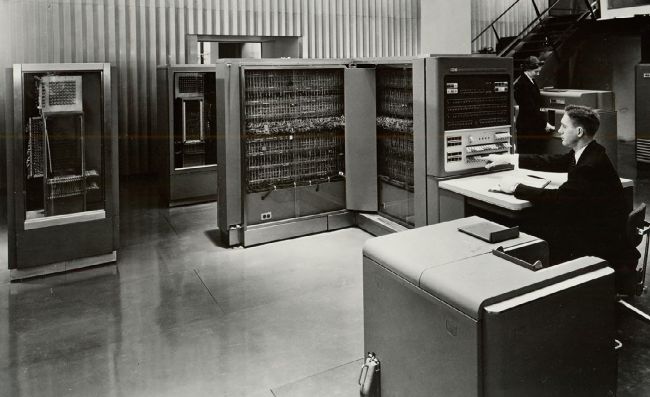

It’s largely forgotten today, but the IBM 704 scientific computer played an important role in kick-starting the FORTRAN project.

CREDIT: IBM

If you want to try your hand at coding in FORTRAN 1957-style, you’re not going to find an IBM 704 FORTRAN compiler. However, with the exception of removing some of the original FORTRAN’s 704-specific instructions, each version of FORTRAN retained most, but not all, of the instructions of its predecessors for backwards compatibility. So, you can use a more modern compiler, but only use the original instructions, and avoid using any that have been deleted more recently. Perhaps the most wellrespected FOSS compiler is GFortran (GNU Fortran), available in the main repositories. Instead, if you want an immediate way of trying out some FORTRAN code, perhaps before moving to a locally-installed solution, use the online Try It Online resource (https://tio.run), which enables you to see the output from your code immediately, and actually uses the GFortran compiler.

FORTRAN AND EXASCALE COMPUTING

The Top500 list, published twice each year, identifies the world’s fastest 500 supercomputers, and currently shows the 8,699,904core Frontier, at the DOE/SC/Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the USA, in the top spot. It’s the only computer ever to have exceeded 1EFLOPS, that’s one quintillion (1,000,000,000,000,000,000) floating point instructions per second, as measured using the LINPACK benchmark.

With so much performance at your disposal – 100,000 times that of top-end gaming PCs – choosing an appropriate language is important in making the most of it. So, it’s interesting to note that pretty much everything you read about Frontier’s software refers to just three languages: C, C++ and FORTRAN. And this isn’t a oneoff. Since the first ever stored program computer, we’ve waited 74 years for the first exascale computer, but others are close on its heels. For example, the forthcoming El Capitan supercomputer, housed at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, has a design speed twice that of Frontier, while Aurora, at the Argonne National Laboratory, is expected to exceed that 2EFLOPS figure. And, while not much has yet been said about El Capitan’s supported languages (but we can guess), like Frontier, Aurora will be programmed in C/ C++ and FORTRAN. Surely there can be no better testimony to this language of the ’50s than it powering the world’s most demanding applications in 2023?