Take a bow

Final Harvest: so long, farewell and amen.

CARSTEN WINDHORST

JOHN LEES’ BJH

VENUE ISLINGTON ASSEMBLY HALL, LONDON

DATE 28/05/2023

It is, as the T-shirts on the merchandise stand read, “A Farewell To Touring”. At 76, John Lees has decided that it’s time for a well-earned rest from the rigours of the road. There will, he’s stated, still be occasional dates and a new album, but nonetheless tonight carries an air of pathos as one of the staples of British progressive rock begin to rein in their activities. Lees wants to “go out on a high”, and does, especially when the encore of Hymn raises a previously sedate Sunday night audience to their feet with some hollering and air-punching. At the same time, a heart of stone would be required to not hear the poignancy as the band’s characteristically gentle classic Galadriel offers the line, ‘Oh, what it is to be young.’

“John Lees has that David Gilmour quality of making each note count, and of knowing how to bring a solo down from a peak gracefully.”

The Oldham oracles have soldiered on through the vagaries of fashion and fate, first as their early-70s success was tilted by punk’s reset, and later after the death of key member Woolly Wolstenholme. In the late 90s, BJH split into two factions, the Les Holroyd one and this one, which has played to huge audiences in

Germany and across Europe. The setlist, while nodding to more recent works like North, sensibly draws on their best-loved Lees-penned material, opening with Child Of The Universe from ’74’s Everyone Is Everybody Else. Its narrative concerning the innocent who are affected by other people’s wars remains as relevant as ever. Poor Man’s Moody Blues has always been a Marmite choice in the band’s catalogue: what was once conceived as a throwaway joke in response to critics has arguably come to stick more than was intended. Still, as bassist Craig Fletcher offers, it’s possible The Moody Blues, exponents of a similarly grandiose melancholy, refer to themselves in private as “the rich man’s Barclay James Harvest”.

It’s the skinny-jeaned Fletcher who, oddly, stands stage centre and, as well as tackling around half the vocals, is in charge of betweensong stage banter. There’s perhaps rather too much of this, as the atmosphere is repeatedly disrupted by chirpy jokes and lengthy explanations of what the songs are about. “I used to look like [Bay City Rollers singer] Les McKeown, now I just look like [TV presenter] James May,” he quips.

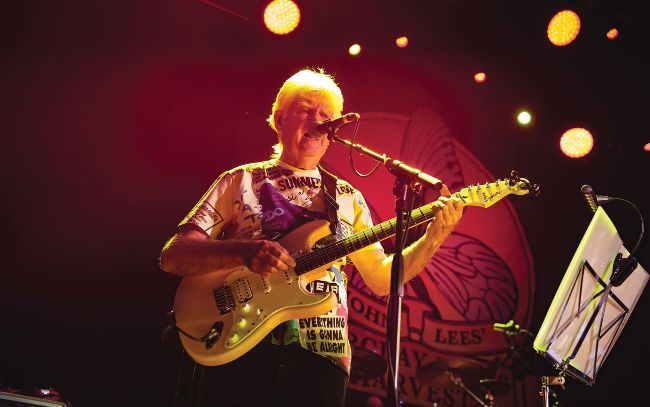

Lees, meanwhile, holds stage right, generally a self-effacing, reticent character. His voice however grows stronger and more affecting as the evening develops, and the tone and timbre of his guitar solos are exquisite. His playing has that David Gilmour quality of making each note count, and of knowing how to bring a solo down from a peak gracefully. It contrasts with his shirt, a surprising option, which is of a loudness somewhere between pop art and punk rock.

She Said takes that Moodies-adjacent vibe and unapologetically redefines epic, while Cheap The Bullet reminds us that around 1990 the outfit had a brief flirtation with MTVfriendly plush rock, all glossy videos and airbrushed hair. The pomp and circumstance return for For No One and Suicide?, the latter leavened by Lees’ preamble, wherein he recalls dropping an expensive state-of-the-art microphone off the roof of Stockport’s Strawberry Studios during the sessions. Medicine Man is much extended and allows some showcase solos from keyboardist Jez Smith and Fletcher. Drummer Kevin Whitehead is impressive all night.

The climax comes with the pairing of The Poet and After The Day, from Barclay James Harvest And Other Stories, which builds from brooding to busting out all over. Lees’ guitar across the crescendo is not so much gently weeping as wailing like Mahalia Jackson. In his own diffident way, it’s Lees raging against the dying of the light. Everything that made Barclay James Harvest moving and meaningful to so many across the decades is in there.

Inevitably the encore begins with Mockingbird, the tender 1971 melody as delicate as it is indissoluble. The audience sway from side to side, memories of long-gone love affairs no doubt flooding their synapses, ghosts smiling benevolently. And then Hymn shifts the mood to one of celebration, everyone leaping from their pews to stand, and to applaud John Lees’ life in music as much as this specific gig, which serves as testament and tribute to the band’s half a century-plus of placid, temperate power.

CHRIS ROBERTS

Craig Fletcher kicks off.

A last chance to bask in the spotlight for John Lees.

Jez Smith keeps his head down.

The band perform a Hymn to the past.

Sterling work from Kevin Whitehead.

The man. The legend. The surprisingly loud shirt.

DAVE HOLLAND

VENUE SYMPHONY CENTER, CHICAGO, IL, USA

DATE 12/05/2023

He was part of Miles Davis’ landmark

Bitches Brew album, name-checked by Bill Bruford as a dream band member and has recorded and performed with a ‘who’s who’ of jazz and rock artists over a six-decade career. By the time he arrives at Chicago’s Symphony Center, bassist Dave Holland is regarded as one of the most loved and respected musicians on this planet.

The room is spacious, obviously built for orchestras. But tonight, the Center has been converted (figuratively) into an intimate jazz club for two sets, with Holland playing as part of both a duo and a trio. Both performances are highly engaging, and Holland has the audience in his hands from the very first note.

The first set is Holland with legendary pianist Kenny Barron, who possesses his own multi-decade CV. The two fill up a massive amount of space, and no drummer is needed to convey the musical message. Holland and Barron trade easygoing solos. Their sound personifies quiet intensity and brilliant interplay as the duo breeze through a set that includes Seascape and Waltz For Wheeler. It’s the ideal way to draw in and engage the crowd, who hang on every note.

Holland returns with guitarist Kevin Eubanks and drummer Eric Harland. The goal, according to Holland, is to play one continuous jam without stopping, using original compositions as guides. This lasts exactly one song before some of the crowd politely inform Eubanks that they’re unable to hear him properly. Clearly, the guitarist’s aim was to keep things lowkey and not draw excess attention to himself. But, after grinning sheepishly and turning himself up slightly, the crowd signal their approval, the ship rights itself, and the band dive into the rest of their set without a hitch.

Once again, the musical interplay is readily apparent. Holland has no trouble sharing the spotlight. Eubanks’ chords smoulder underneath Holland’s lead lines, then burn when he comes forward to lead the composition’s direction. Harland, meanwhile, grooves hard, giving the music the ‘swing’ it needs. His snare drum work is exceptional. When Harland solos, Holland’s bass darts in and out between the drummer’s licks, giving the rhythm section an extra layer of power. Holland continues to do what he does best – providing the groove and anchor the band needs to help propel things forward. It’s easy to see why the man is a legend. There is no disputing the chemistry this band have.

Like Holland’s set with Barron, the trio play what feels like one of the fastest hour-long shows imaginable. The band even rebel and give the audience one more tune than they were supposed to. It’s the perfect way to end a highly satisfactory evening.

CEDRIC HENDRIX