Finding Neverland

The early 2000s were a time of change and self-discovery for Marillion. Following the success of their early crowdfunding experiment on Anoraknophobia, they returned to the studio to create an ambitious follow-up that would land them back in the UK Top 10. As Marbles reaches its 20th anniversary, the five-piece recount the falling outs, ‘happy drugs’ and tales of Neverland that led to the modern-day version of the band we know and love.

Words: Philip Wilding

Images: Carl Glover

"The past is foreign country, they do things differently there.” It’s unlikely that LP Hartley, author of The Go-Between, was referring to experimenting with ecstasy for the first time in your late 40s while working on a new album, but this is the seemingly alien landscape that singer Steve ‘H’ Hogarth found himself in as Marillion began the lengthy and ultimately rewarding process of making the hugely creative Marbles.

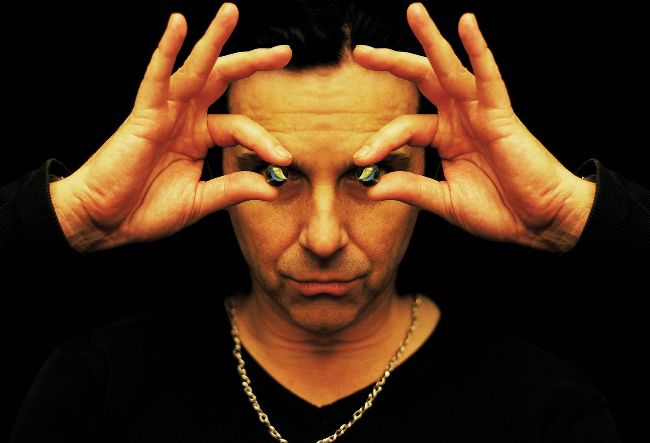

“Let me tell you: ecstasy –it’s the way to go, for a little while at least,” says Hogarth, you can almost see the twinkle in his eye.

He’s on the phone at home and we’ve been chatting about the band’s mindset post-Anoraknophobia and its industry-changing, crowdfunding model. A similar question to other members of Marillion had them reflecting on the lean commercial years of the Castle albums like Marillion.com, and how Marbles had brought them blinking back into the creative and critical light. But not Hogarth.

“I think this was the record where I did change how I wrote, absolutely.”

Steve ‘H’ Hogarth

“I thought you said the pub was this way?” The path to Marbles wasn’t always clear.

“Sometimes you know you might be catching lightning in a bottle, and as soon as we had some of it written, we knew we were on to something good.”

Mark Kelly

“In a sense, it was quite an interesting time. I remember being down in the West Country working on [closing track] Neverland. Just, you know… just in love with everything. But particularly Mark’s opening chords for that song and all of us being so in love with it that we didn’t want to fuck the rest of the song up, so we just kept going round and round, and of course, being somewhat high on ecstasy. I was quite happy to go round and round…”

It’s 2002 and Marillion are no longer in a state of flux. The 90s started with the promise of Holidays In Eden, but their major-label dreams were dashed by the middle of the decade after EMI shrugged them off following the prolonged and poorly received (by the label, at least) Brave sessions and album. Even though the band rallied with the career-defining Afraid Of Sunlight, it wasn’t enough to keep them cloistered as a major label priority. The end of the decade saw them deliver three albums in as many years, only to find refuge in a new kind of crowdfunding model that not only kept them propped up as a working band, but gave them the breathing space to create new music, too. It was no coincidence that Anoraknophobia was a creative leap from Marillion.com, but Marbles was to be something else again.

“Some albums are key moments in our musical journey,” says Pete Trewavas, “and I think Marbles is definitely one. I think Anoraknophobia might have been one, too, because having done that, it allowed us to relax. It gave us breathing space to recognise a bit more of our original DNA and what made us the band we were. You forget that when you’re on this musical treadmill sometimes.”

“We were feeling very positive at that point,” adds Steve Rothery about the period leading up to the recording of Marbles.

“With Anoraknophobia being so well received, it finally felt like we’d escaped the clutches of independent labels. And, you know, could concentrate on trying to make a world-class record. We went down to Sil Willcox’s place outside of Bath to work –he managed the Stranglers and the Wurzels –and we drank scrumpy [strong cider] and played around with the songs there. That’s where You’re Gone came from [see box-out on p39], my faffing around with the Logic sequencer where you can memorise chords and play them with one finger, which is about my level on a keyboard.”

Mark Kelly plays us the opening chords to Neverland. He’s seated in his home studio surrounded by keyboards, gold discs on the wall behind him. We’re chatting over Zoom when he plays what would become the opening to a song that’s still a staple of the band’s live set more than two decades later.

“I liked that place near Bath,” he says. “A cottage more than a rehearsal space, really, but that’s where I came up with these chords for Neverland; the components, at least. And everybody was like, ‘Oh, that sounds interesting.’ That was right from the start and then later we had things like Invisible Man, which was really exciting. Sometimes you know you might be catching lightning in a bottle, and as soon as we had some of it written, we knew we were on to something good. There was definitely a good atmosphere around the band at that time.”