A POTTED HISTORY OF LINUX

Or how a 21-year-old’s bedroom coding project took over the world and a few other things along the way.

By Neil Mohr

© MAGICTORCH

LINUX ONLY EXISTS because of Christmas: On January 5, 1991, a 21-year-old computer science student, who was currently living with his mom, trudged through the (we assume) snow-covered streets of Helsinki, with his pockets stuffed full of Christmas gift money. Linus Torvalds wandered up to his local PC store and purchased his first PC, an Intel 386 DX33, with 4MB of memory and a 40MB hard drive. On this stalwart machine he would write the first ever version of Linux. From this moment on, the history of Linux becomes a love story about open-source development, software freedom, and open platforms.

Previous to walking into that computer store, Linus Torvalds had tinkered on the obscure UK-designed Sinclair QL (Quantum Leap) and the far better known Commodore Vic-20. Fine home computers, but neither was going to birth a world-straddling kernel. A boy needs standards to make something that will be adopted worldwide, and an IBM compatible PC is a good place to start. But we’re sure Torvalds’ mind was focused more on having fun with Prince of Persia at that point than developing a Microsoft-conquering kernel.

Let’s be clear: A 21-year-old, barely able to afford an Intel 386 DX33, was about to start a development process that would support a software ecosystem, which in turn would run most of the smart devices in the world, a majority of the Internet, all of the world’s fastest supercomputers, chunks of Hollywood’s special effects industry, SpaceX rockets, NASA Mars probes, self-driving cars, and whole bunch of other stuff besides. How the heck did that happen?

TO UNDERSTAND HOW Linux got started, you need to understand Unix. Before Linux, Unix was a well-established operating system standard through the 1960s into the 1970s. It was already powering mainframes built by the likes of IBM, HP, and AT&T. We’re not talking small fry, then—they were mega corporations selling around the globe.

If we look at the development of Unix, you’ll see certain parallels with Linux: Freethinking academic types who were given free rein to develop what they want. But whereas Unix was ultimately boxed into closed-source corporatism, tied to a fixed and dwindling development team, eroded by profit margins and lawyers’ fees, groups that followed Linux embraced an open approach, which enabled free experimentation, development, and collaboration on a worldwide scale. Yeah, yeah, you get the point.

Back to Unix, which is an operating system standard that started development in academia at the end of the 1960s as part of MIT, Bell Labs, and AT&T. The initially single or uni-processing OS, spawned from the Multics OS, was dubbed Unics, with an assembler, editor, and the B programming language. At some point, that “c” was swapped to an “x,” probably because it was cooler, dude.

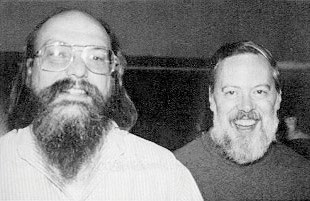

Ken Thomas (left) and Dennis Ritchie are credited with creating much of the original UNIX, while Ritchie also developed the C language as well.

Later, someone needed a text editor to run on a DEC PDP-11 machine. So, the Unix team obliged and developed roff and troff, the first digital typesetting system. Such unfettered functionality demanded documentation, so the “man” system (still used to this day) was created with the first Unix Programming Manual in November 1971. This was all a stroke of luck, as the DEC PDP-11 was the most popular mini-mainframe of its day, and everyone focused on the neatly documented and openly shared Unix system.

In 1973, version 4 of Unix was rewritten in portable C, though it would be five more years until anyone tried running Unix on anything but a PDP-11. At this point, a copy of the Unix source code cost almost $100,000 in current money to license from AT&T, so commercial use was limited during the 1970s. However, moving into the 1980s, costs rapidly dropped, and widespread use at Bell Labs, AT&T, and among computer science students propelled the use of Unix. It was considered a universal OS standard, and in the mid-1980s, the POSIX standard was proposed by the IEEE, backed by the US government. This makes any operating system following POSIX at least partly if not largely compatible with other versions.