THE MOJO INTERVIEW

The Roots’ Renaissance Man of Rhythm on Fallon, Sly, Amy, addiction (to vinyl), Pete Townshend’s J Dilla fetish, and what makes him run so hard, so fast. “You don’t figure out what’s next,” says Questlove. “You just do it.”

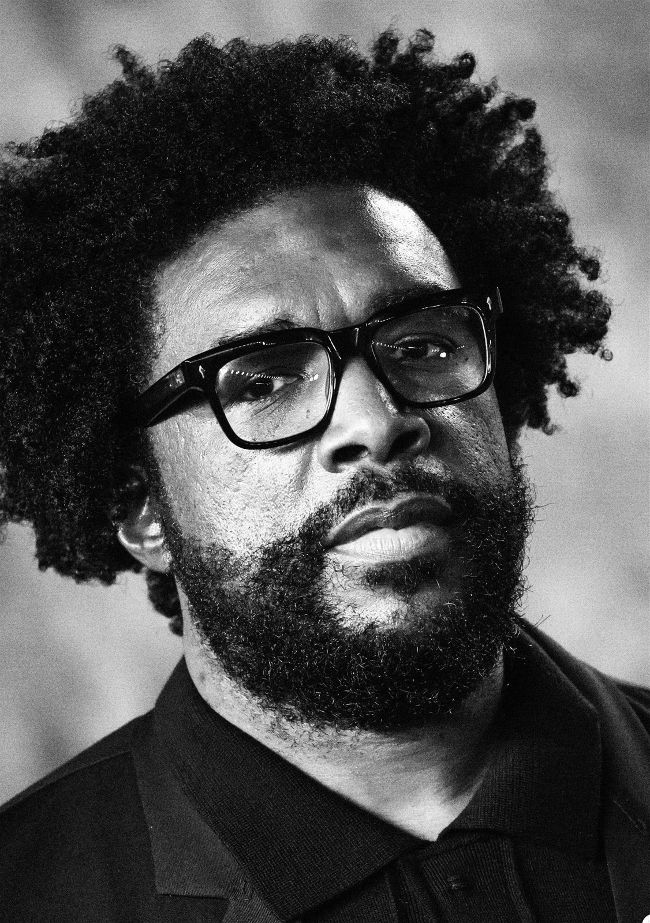

Interview by DAVID FRICKE • Portrait by LEON BENNETT

Leon Bennett/Getty, Getty

‘‘I’M PAST DEADLINE,” QUESTLOVE confesses with a smile and a sigh as he looks intently at the television screen suspended over a dining table in his apartment. The picture-window view from his perch in a lower-Manhattan skyscraper goes to Brooklyn and beyond. But the producer, DJ, author, filmmaker and founding drummer of hip-hop institution The Roots is glued to the new, opening sequence – a rapid-fire montage of interview clips and kinetic live footage – for his documentary on the kamikaze R&B genius Sly Stone, the follow-up to Questlove’s 2021 Academy Award-winning debut as a director, Summer Of Soul. WAY

“I’m realising that every project I work on has a surprise element,” he says, turning off the TV and jumping right into three, winding hours of knockout anecdotes, acute musical analysis and candid, personal reflection for MOJO. “With Summer Of Soul, you learn one thing: ‘Oh, I didn’t know a music festival happened in Harlem [in 1969].’ But you also learn that black joy is as important as the black tears and bloodshed of the civil rights movement.” In turn, “This Sly doc isn’t really about Sly,” Questlove warns. “It’s about why artists self-sabotage.”

Questlove, 53, is too busy and jubilant in the workload to get in his own way – literally “the king of ‘yes’” as he puts it in his latest book, Hip-Hop Is History, a roller-coaster guide to the author’s life in the music since he was six years old, hearing the Sugarhill Gang’s Rapper’s Delight on the radio in Philadelphia. Today, Questlove reveals that within two weeks of winning his Oscar, he agreed to direct another six films. Meanwhile, The Roots are “damn near 80 per cent done” with their first LP in 10 years and have “four songs on the back burner” for a project with fellow Philly icon Todd Rundgren. And that’s on top of Questlove’s productions for other artists, DJ bookings and The Roots’ 15 years on TV as the house band for talkshow host Jimmy Fallon, the last 10 of them on The Tonight Show.

Born Ahmir Thompson, Questlove comes from doo-wop royalty with bonus hip-hop cred. His father was the namesake vocal star of Lee Andrews And The Hearts – Long Lonely Nights (1957); Tear Drops (1958) – while an album by Congress Alley, his parents’ ’70s funk band, was sampled by Dr. Dre for his 1992 blockbuster, The Chronic. Questlove attended arts and music schools but was already road-tested as his dad’s drummer and bandleader when he started freestyling on the Philly streets with a classmate – rapperlyricist Tariq Trotter, AKA Black Thought – creating a fusion of live drums and quick-draw lyricism they eventually called The Roots.

Questlove talks the way he writes books and linernotes for Roots albums: vigorously expansive and colourfully digressive with lots of star names dropped in. He remembers Miles Davis walking into his high school one day and grabbing another student, organist Joey DeFrancesco, to go on tour. And a story about D’Angelo – Questlove co-produced the singer’s 2000 smash, Voodoo – somehow leads to the drummer’s “almost 20 minutes yesterday” on the phone with Pete Townshend, mutually raving about mixtapes by the late producer J Dilla. The Who’s guitarist is “a legit Dilla head,” Questlove says, laughing, “almost past me.”

Where does the name Questlove come from?

The Roots went through a bunch of phases. We started as Radioactivity – Tariq was T Metaphor, I was A Sample. That didn’t last long. Tariq rechristened us Black To The Future – he was Hawk Smooth and I was Divine Technician. He named me that, and I didn’t like it. The day that De La Soul Is Dead came out [in 1991], we said, “We’re going to take this seriously.” Tariq goes, “I’m Black Thought,” and we changed our name to the Square Roots. He’d written down some other names for the group, and the last one was just a question mark. I took that. But when we did local press, everyone thought my name was Mark. Or “So, Brother Question…”