Movements Of Visionaries

Fifty years ago, electronic music got a new beat when Tangerine Dream released Phaedra. The pioneering German group’s fifth studio album saw the Berliners relocate to the English countryside, and its motorik grooves played a key role in what was being defined as krautrock. We look back on the story behind one of the greatest experimental electronic albums of all time, its legacy and the synthesiser that informed its sound.

Words: Chris Wheatley

Christopher Franke, Peter Baumann and Edgar Froese, circa 1973.

Image: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

November 1973. Frayed bell-bottoms were the height of fashion; Pink Floyd culminated their Dark Side Of The Moon tour and the Mariner 10 spacecraft blasted off on a mission to send back the first-ever photos of Mercury to an eagerly awaiting Earth. Meanwhile, in the little Oxfordshire village of Shipton-on-Cherwell, three visionary musicians armed with cutting-edge technology were about to alter the musical landscape forever. Edgar Froese, Peter Baumann and Christopher Franke –otherwise known as Tangerine Dream –flew from Berlin in Germany to Richard Branson’s The Manor to record an album that would change their lives and that of the many people who would hear it. It was a record that was to achieve great things, blowing minds with its sheer invention and inspiring decades of electronic music.

“We never really discussed the music much. It was more like: have a good joint and then start playing.”

Peter Baumann

For Branson, it was a propitious time. Virgin Records was in the second year of its existence and riding high on the phenomenal success of Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells. The label’s mail order service was in full swing, providing fans in England with advance access to the cream of American imports. Never one to rest on his laurels, the entrepreneur had travelled in person to Germany to recruit his latest act. By the time they signed to Virgin, Tangerine Dream had already released four albums via German experimental label Ohr. They’d also undergone multiple changes in personnel, with founding member Edgar Froese the only constant. For their previous two long-players, however, Zeit (1972) and Atem (1973), they’d settled on what is now considered their classic line-up.

Froese was the group’s creative powerhouse and polymath; an instinctive musician who’d also studied painting and sculpture at the Berlin Academy of Arts. On tour in Spain with his first band, The Ones, Froese had performed a special concert for the surrealist painter Salvador Dalí. It was a meeting that infused him with a passion for experimentation. Returning to Germany, he formed Tangerine Dream in 1967 with a longsince forgotten line-up of Lanse Hapshash (drums), Kurt Herkenberg (bass), Volker Hombach (sax, violin, flute) and Charlie Prince on vocals. By the time Christopher Franke joined in 1971, after a stint as drummer for The Agitation –later renamed Agitation Free – Steve Jolliffe, Klaus Schulze and Conrad Schnitzler had all passed through the band’s ranks.

Peter Baumann also came on board that year, at the crucial point when the band were shifting from guitars to electronics. For Baumann, a career in music was never planned.

“Oh, no, not at all,” he admits. “Everything that happens in my life is an accident. And it was a very simple story: I had a buddy in school, and we were just chatting. He said, ‘I’m playing in a band, why don’t you come along and listen?’ So I went. They had a bass player, guitar player, vocalist and drummer, but no keyboard. So I said, ‘Why don’t I go on keyboards and join you?’ And that was it.”

Primarily a covers band, this was a good experience for Baumann, but not fulfilling. It was another accident of fate, a chance meeting, that initially led to his involvement with Tangerine Dream.

Tangerine Dream performing at Coventry Cathedral, Warwickshire, October 4, 1975.

MICHAEL PUTLAND/GETTY IMAGES

“Tangerine Dream was not about personalities. None of us was a star or a special person. It was always the music that was front and centre”

Peter Baumann

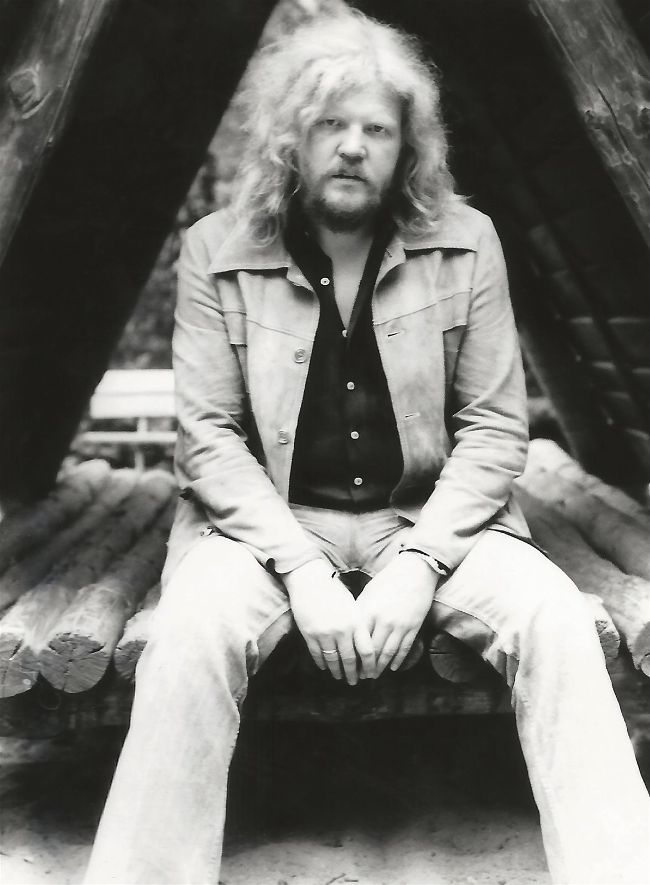

Founding member Edgar Froese, the only constant in the band, pictured in 1973.

©EASTGATE MUSIC & ARTS ARCHIVE BERLIN/MONIQUE FROESE

“I was at a concert –Emerson, Lake &Palmer,” he recalls. “They started late, so I began to talk to the folks behind me. There was a guy with long, dark hair named Christopher. We were chatting about what we were doing. He said he played in a band. I said, ‘I do some experiments with music as well.’”

Bonding over a shared love of instrumental records, the two exchanged details and, a week later, Baumann received a note from Franke urging him to get in touch as they were looking for a new keyboard player.

“So I called up,” recalls Baumann, “and about a week later, they invited me to bring my keyboard and meet them at a rehearsal room. The rest is history.”

Over their following two albums, Zeit and Atem, Tangerine Dream set about exploring new sounds.

“The music was evolving, intuitively,” says Baumann. “You’re always trying new things and you say, ‘Hey, that seems to work’, but we never really discussed the music much. It was more like: have a good joint and then start playing.”

With Phaedra, however, that changed. “The major difference was that it was the first record where we had a Moog synthesiser,” remembers Baumann. “That was very unique at the time, and it really set the flavour for the main piece.”

The synthesiser in question came to the group via an unusual path. Sometime in 1969, The Rolling Stones had purchased a complete modular system from Moog, one of the very first commercially available. The Stones’ experiments with the nascent technology ultimately led nowhere. Dissatisfied, they sold their equipment to the Hansa Studio in Berlin, an establishment that would later become famous through its use by David Bowie, Iggy Pop and others. Back in 1973, Hansa accepted an offer for the Stones’ old Moog from Tangerine Dream’s Christopher Franke. A bargain at only $15,000 –an equivalent of about £90,000 in today’s money.