Ubuntu at 20

Ubuntu at 20

A decade on from celebrating a decade of Ubuntu, Neil Mohr wonders where all the time has gone.

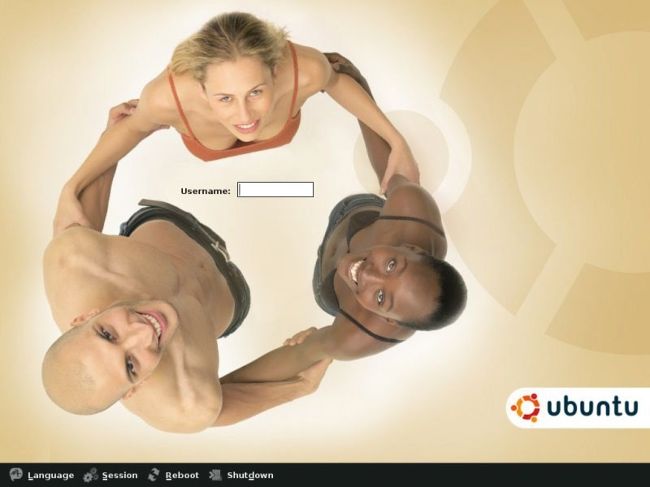

So, that Ubuntu logo with the three dots – it’s people holding hands, from the original Warty login.

CREDIT: Wikimedia/Ubuntu

Without Ubuntu, the current Linux landscape would be unrecognisable. Back in October 2004, the first 4.10 (2004.10) release of Ubuntu, with its intriguing Warty Warthog code name, leapt from obscurity to being one of the most downloaded Linux distributions of the year. And that’s in spite of it sporting a less-than-attractive brown wallpaper. Perhaps the motto of “Linux for Human Beings” might have been on to something – radical departures such as enabling user accounts to make system-wide admin changes flew in the face of the classic novice-baffling Linux behaviour of the time. Being backed by an actual for-profit organisation was another departure, rather than the rag-tag hacking teams or lone coders that had preceded it, with those successes coming more by accident than by design. It seemed Ubuntu was set up for success from the start. The vision came from Mark Shuttleworth, a Debian developer who benefited from the dotcom bubble, which turned him into a multi-millionaire and happy philanthropist. His passion to give back to the open source community that had helped establish him, helped establish Ubuntu – a Zulu word meaning humanity to others – a Linux distro made for humans.

He was clearly on to something, as this human-first approach created the most popular distro of all time, which went on to directly spawn more respins than anything before or since, alongside possibly more controversies than any other project has experienced, too! Fun times for all. So, after 20 years of gently shifting-hue backgrounds, let’s look at how Ubuntu has developed over the decades, the controversies that exploded with that and the players behind it.

Slack and snacks

Cape Town, South Africa, early ’90s. A young student is sitting late at night in the University of Cape Town’s computer lab, a pile of snacks on his right and a pile of Slackware install floppies on his left. He doesn’t know it yet, but he’s about to become a major force in the Linux open source world; he’s also going to be in big trouble, as he needs to reinstall Windows on the PC before the labs reopens, too. That student was Mark Shuttleworth, and like so many before and since, free access to open source changed his life completely.

Shuttleworth didn’t have his own PC, so the only way to try Linux was on university equipment. He got involved in a project to hook up the university to the internet and started using Debian. Realising Apache wasn’t available, he became a Debian developer, maintaining the first Apache package. By the mid-’90s Shuttleworth had graduated with a degree in finance and information systems and established his company, Thawte, in the security and verification sector, built on Debian, Apache and MySQL. It was very successful and was bought by Verisign in 1999 for US$575 million ( just over US$1 billion in today’s money).

So, what’s a 27-year-old multi-millionaire supposed to do with all his time and money? Other than pay to be the first South African in space… Luckily for the world, Shuttleworth has a strong philanthropic streak. He’d already established the Shuttleworth Foundation and told us in LXF71, “I kind of need to get rid of everything that I’ve acquired. I’m quite keen to do that in my lifetime.” (You can read part of the interview on p.42.)

SPINS, SPINS AND MORE SPINS!

Why reinvent the wheel when you can just respin it? It’s testament to the success and appeal of Ubuntu just how many respins have been created over the years. According to the Linux Distribution Timeline project (https://distroware.gitlab.io), almost 90 distros – many now unmaintained – have been spun out from Ubuntu. Some can be as straightforward as running an alternative desktop environment, others are themed, such as Hannah Montana Linux, or dedicated to a specific task, such as Ubuntu Studio, while a number offer a completely redeveloped experience, such as Linux Mint.

There are two distinct spins of Ubuntu: there are classic Ubuntu flavour spins, then everything else. Flavours (https://ubuntu.com/desktop/flavours) are official spins of Ubuntu. These are supported within the Ubuntu community and backed by its infrastructure for builds and deliveries. Kubuntu was the first – this packaged the KDE desktop and associated apps for Ubuntu, rather than Gnome – and it laid the ground for how these flavours are handled, along with their relationship to Canonical and the main Ubuntu project. Other spins, such as Linux Mint, while they might take and use the Ubuntu base repositories, have to build and maintain their own releases and support services such as websites, forums and funding.