BEATING THE BUG

Ian Evenden discovers the history of a problem many think never existed

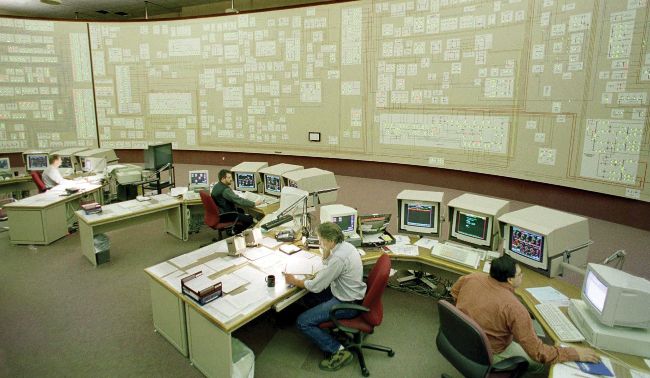

The power grid at the Niagara Mohawk Power Corporation control facility in Buffalo, NY, December 28, 1999, during the final phase of Y2K testing.

©JOE TRAVER/ GETTY IMAGES

There was no human sacrifice. Dogs and cats did not live together. The only mass hysteria was in the media. And unlike Ghostbusters, the Millennium Bug, also known as the Y2K problem, was very real. It was only through a lot of hard work on the part of programmers and IT contractors across the world that bad things didn’t happen. And it’s not as if we weren’t warned about it years in advance.

For those under the age of 40, here’s the condensed version: as the year 2000 approached, warnings increased in the press that, at one second past midnight on January 1, all computers would experience an integer overflow; planes would fall out of the sky, and nuclear reactors explode as a result of catastrophic computer failures linked to the date rollover. This didn’t happen, as most computers had been “fixed”—some properly, and others in a way that merely postponed the problem. There were effects, some detrimental and others just annoying, from a date-related integer overflow in 2000, just as there were effects from such bugs before that year. In fact, we continue to feel the effects today. Here’s how Y2K unfolded…

WHERE IT ALL BEGAN

First, Oppa Gangnam Style! The Korean pop hit that taste forgot thrust its way manfully through the eardrums of the world and racked up 2,147,483,647 views on YouTube in 2014. This particular figure was the largest number of views YouTube’s backend could support back then, as the site was written with 32-bit integers in mind. A quick upgrade to 64-bit integers later, and Psy’s terrifying total could continue its unstoppable upsurge toward the new ceiling of over 9 quintillion views. The basic problem here, an integer overflow, is essentially the same as the Y2K problem.

It all boils down to programmers taking a shortcut, and representing a year with two digits instead of four. This happens absolutely everywhere, despite International Standard ISO 8601 specifying that dates should be written as YYYY-MM-DD. Had computers, particularly embedded systems, used this standardized date format, there wouldn’t have been a problem, but computer storage space was once very expensive, and every byte counted, so many programmers used YY-MM-DD, or MM- DD-YY, or DD-MM-YY to save both space and processing time. This all worked fine for a long time, but eventually, due to the way two-digit dates were interpreted, it meant that as 1999 turned to 2000 those systems found themselves in 1900 and, unaccustomed to this time period, either failed or displayed an error.

Another way to think of it is in terms of the odometer in your car. As it passes 99999.9 miles, the final digit clicks around and returns to 0. This causes a cascade reaction through every other digit, returning them all to the same state. It can’t generate an extra decimal place, so instead of 100000.0 you get 00000.0. Your car isn’t, sadly, returned to factory-fresh condition, but this mechanical wrappingaround of the numbers mirrors what happens in a computer.

Peter de Jager, host of the Y2K: An Autobiography podcast and a prolific public speaker on the subject, is often credited with bringing the Y2K problem to widespread attention through a 1993 article in Computerworld magazine, but awareness of the problem goes back further than that. IBM computer scientist Bob Bemer noticed it in 1958 while working on family tree software. In the 1970s, banks offering 30-year mortgages bumped into the problem, while in the 1980s the financial industry was forced to take notice, as bonds with expiry dates beyond the year 2000 were issued. By 1987 the New York Stock Exchange had 100 programmers working on the problem, and had spent $20 million on it. The federal government would go on to spend $8.5 billion.

Psy’s Gangnam Stylevideo on YouTube, showing a seriously impressive 3,931,348,435 views.

© YOUTUBE, WIKIPEDIA,

Employees monitor the National Command Center for Mastercard International, January 3, 2000. No Y2K problems were encountered.

De Jager’s article came about as a result of some persuasive tactics with an editor: “I was at an Association for Systems Management meeting, I think in San Francisco,” he tells us. “And I’m giving a talk on something very mundane, the PC productivity paradox.” This is the slowdown in productivity in the US in the 1970s and 1980s despite rapid development in IT at the time. “There were 300 or 400 people in the room, including this Computerworld editor. When I got home, she called me, said she liked the presentation, and asked me to do an article on it. This is back in the day when print media was huge. The old Computerworld magazines were like an inch thick, and would drop on your desk every week, the Bible of the IT industry. And I said, ‘You have to be kidding. You want me to write about a stupid topic like PC productivity? How about I write about the biggest problem in the IT industry that we’re going to face? The fact that we store the year in two digits, and seven years from now this thing is going to go bellyup.’ She says, ‘Well, OK, you can do that’. It was a little bit of serendipity.”