FILTER REISSUES

Industrial, complex

One of the first albums to be digitally recorded, mixed and mastered is back for a 40th anniversary. There’s soul beneath the sheen, discovers Keith Cameron.

Dire Straits

★★★★

Brothers In Arms

UNIVERSAL. CD/DL/LP/BR

OF ALL the artists to herald the digital age with its shiny new compact disc format, Dire Straits were surely the least likely. Workhorses rather than high-gloss show ponies, they emerged from London’s mid-’70s pub rock circuit featuring two former members of Brewer’s Droop, playing country-tinged blues boogie written by a self-effacing ex-newspaper reporter and school teacher from Newcastle. Mark Knopfler had tried many other jobs before rock’n’roll, and beyond inculcating respect for hard graft and emphasising where his gifts truly lay, none prepared him for leading the world’s biggest band.

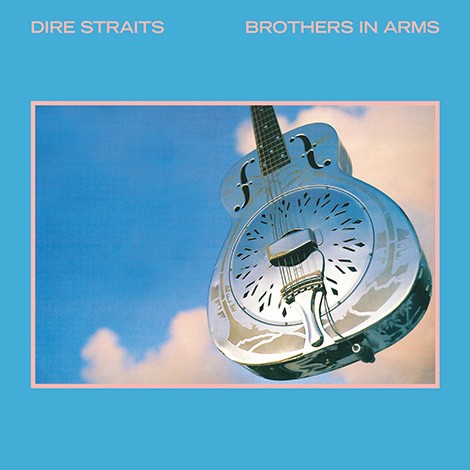

Which is pretty much what Dire Straits became on the back of their fifth album. Brothers In Arms was UK Number 1 for 14 weeks and spent nine weeks on top of the US chart, scooping up worldwide sales of over 20 million, driven by a year-long 1985-86 world tour numbering 248 shows and a string of hit singles, none bigger than Money For Nothing, a Billboard Number 1 turbo-charged by its state of the art computer-animated video, to all intents and purposes an advertisement for MTV – which duly repaid the debt in endless rotation. Thanks to these numbers and legacy, Brothers In Arms ceased to be a mere album and became a pop cultural avatar – imagine a silver 1937 National Resonator guitar slapping you in the face, forever.

It’s ironic that a record which became synonymous with ‘more’ began as an attempt at less. Knopfler was craving a return to roots, after first 1980’s Jimmy Iovine-produced Making Movies had powerfully upgraded the 1978 debut Dire Straits’ backroom choogle, and then 1982’s still-startling Love Over Gold, an epic suite of abstract expansions plotting the geometry of thin air in ways that would be subsequently pursued by Talk Talk and Radiohead. Yet in the interim he’d also made some movie soundtracks – most notably Local Hero, where his theme was as much the star of the film as either Burt Lancaster or the Scottish Highlands – and bought a Synclavier digital synthesizer and hired Roxy Music’s Guy Fletcher to play it. Ergo, essentially, Brothers In Arms: songs like So Far Away and Why Worry are intense miniature dialogues transposed to widescreen and filigreed with the latest tech. The former feels like a dustbowl motorik refugee from Avalon, while the latter’s lonesome melodies and hanging chords were soon acknowledged worthy of an Everly Brothers cover version.

The album’s most minimal song, tellingly Why Worry was also its longest. The Cajun trifle Walk Of Life became a radio perennial but it was never more than a throwaway ditty, and indeed co-producer Neil Dorfsman wanted to do just that; the Knopf said no, he felt its charm, and got his way. Knopfler’s gift was always to see the significance in minor inflections, be they emotional or musical. The Man’s Too Strong, meanwhile, is as low-key as a Celtic-tinged character study of a suspected Nazi war criminal possibly could be.

Deborah Feingold/Corbis via Getty Images, Pete Still/Redferns/Getty

“No mere album but a cultural avatar: imagine a silver 1937 National Resonator guitar slapping you in the face, forever.”

Amid these embroidered cameos land the epic set-pieces: Your Latest Trick whiffs of mid-’70s Dylan jamming with Steely Dan, complete with the Brecker Brothers giving it the full lounge act. Knopfler had worked with them on Gaucho’s Time Out Of Mind, a reportedly stressful experience for him, but this time they were playing to his tune. Ride Across The River is Springsteen gone white reggae for a woolly dogs of war tableau. Better by far is the title track’s haunted battlefield evocation, barely there but speaking louder for it, spiralling upwards like Pink Floyd with warmblood in the veins. In Paul Sexton’s sleevenotes for the deluxe edition, Knopfler reveals the title came from a comment his father had made about the Falklands War and the irony of the Soviet Union backing a fascist junta in Argentina.

Of course, much of Brothers In Arms’ lower-case intrigue is eclipsed by Money For Nothing, and how could it not? The greatest riff Billy Gibbons never wrote; the guest vocal from Sting, literally dragged in off the beach and asked to sing “I want my MTV” to the tune of one of his own songs; and a notoriously jarring lyric. Knopfler was not the first to discover that pop songs aren’t the safest vehicles for hiding an obnoxious narrator, but as a deep fan of Randy Newman he perhaps ought not to have been too surprised when people were offended by his voicing a pair of hardware store workers watching a “little faggot” playing guitar on the televisions they were shifting. Come the Brothers In Arms tour he was already self-censoring, and whatever subversive commentary the song had to offer on the process of fame – a rock star who resented making videos singing a song satirising people who resent rock stars, watching rock stars on video – was rendered moot.

This fortieth anniversary version is unlikely to shift the critical dial on a record about which most people have long since made a decision. There are no studio out-takes suggesting alternate paths, which is a shame, as the sleevenotes trace the pre-production process from Knopfler’s west London mews to Ray Manzanera’s studio in Surrey and thence to George Martin’s fabled AIR outpost in the Caribbean. Almost all drummer Terry Williams’ contributions in Montserrat were replaced by jazz session ace Omar Hakim, and if they still exist somewhere they’re not here. At least Terry was back on the stool for the 1985-86 tour, which provides the only real inducement for diehard fans to buy: the deluxe edition has the entire unreleased San Antonio concert from August 16, 1985, a faithful representation of how far a groovy little rock’n’roll band had gone in less than 10 years, the two remaining originals – Knopfler and John Illsley – surrounded by extra keyboardists, saxophone and percussion, their songs appended with yawning intros and multiple crescendos that threaten to secede from the thing they’re ostensibly bringing to a close, not a single note out of place. Amid it all, Knopfler’s virtuosity remains somehow both transcendent and earthy, his perennial saving grace.

By the end of that 12-month tour, Mark Knopfler was as tired of Dire Straits as anyone. Five more years elapsed before the follow-up to Brothers In Arms, 1991’s scruffier, even longer On Every Street, after which he called time on the whole dog and pony show, fed up with being famous for merely playing his guitar on that damn MTV. “Success I adore,” he told Sylvie Simmons in a 1996 interview. “As far as I can see, fame is just a waste-product of success.”